The consonant phoneme inventory of Proto-Indo-European, as usually reconstructed. IPA transcriptions are based upon their manifestations in the surving daughter languages, as exemplified in e.g. SoundCorrespondences.html and discussed in detail below.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Pre-velar | Velar | Labiovelar | Uvular or Pharyngeal | Glottal | |

| Stops: voiceless | *p [pˉ] | *t [tʰ] | *ḱ [k̟ʲʰ] | *k [kʰ] | *kʷ [k̟ʷʰ] | ||

|

voiced unaspirated

|

*b [b] (?) | *d [d] | *ǵ [g̟ʲ] | *g [g] | *gʷ [gw] | ||

|

voiced aspirated

|

*bʰ [bʱ] | *dʰ [dʱ] | *ǵʰ [g̟ʲʱ] | *gʰ [gʱ] | *gʷʰ [gʷʱ] | ||

| Nasals | *m [m] | *n [n] | |||||

| Voiceless fricatives | *s | *h₂ [ħ]~[ɐ̥] | *h₁ [h]~[ɘ̥] | ||||

| Frictionless continuants | *l [l], *r [r] | *y [j] | *w [w] | *h₃ [ʕ̰]~[ɔ̰̆] |

Many modern Indo-European languages have quite a large number of fricatives, but in Proto-Indo-European the only fricatives that are reconstructed in my simulations are *s and the so-called “laryngeals” *h₁ (possibly [h], at an early stage) and *h₂ (probably [ħ], or possibly [χ], at an early stage). The third “laryngeal” *h₃ is, in the analysis given here, an approximant not a fricative. However, the phonetic nature of the “laryngeals” is unclear and has been extensively debated; for a justification of the proposals given here, see the data and discussion in laryngeals.html. The question of their phonetic nature is inextricably entwined with the Proto-Indo-European vowel system, which I present in PIEvowels.html. In this section I'll just give some examples, to be followed by more detailed discussion in later sections.

The richer systems of fricatives in modern Indo-European languages arise from later sound changes, especially various kinds of lenition of ancestral PIE stops, as in:

*s > [s] in most Indo-European languages, so we are fairly confident that it was pronounced as [s] in Proto-Indo-European. However, sometimes *s lenited to [h], for example:

*sed‑ “sit” > Ancient Greek ἕζομαι [hétsomɑɪ]

*seh₂l-s “salt” > Ancient Greek ἅλς [hals], Welsh halen

*somh₁-o- [somo] “same” > Ancient Greek ὁμός [homós], Persian هم [ham], Pashto [ham]

*septm “seven” > Pashto هفته [hapta] “week”, Persian هفت [haft]

Due to the phenomenon of the “mobile s” (a kind of [s]-prefixation), a number of Proto-Indo-European words are found in two forms: one with an initial [s] and the other without, with corresponding variations in their historical outcomes. Examples in the Audio Etymological Lexicon are:

English shear < *s-ker- vs *ker-mn > Persian چرم charm “leather”

shoot < *s-keud- vs. *keud‑ > Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian kidati “to tear/break”

show < *s-keuh₁- [skou] vs. *kouh₁-is [ko:his] > Marathi कवि [kavi] “poet”, Ancient Greek κοέ(ω) [koe] “be aware of”

spark < *s-pergʰ- [spɘrgʱ] “sprinkle” vs. *pergʰ- [pɘrgʱ] > Sanskrit पर्जन्य Parjanya “(god of) rainfall”, Marathi Parzhanya, possibly Lithuanian Perkūnas “(god of) thunder”. (Some etymologies derive Perkūnas from a different root, *perkʷ- “oak”, as in Latin quercus, but I am not 100% convinced of that because the semantic link between rain and thunder is even more natural than the association between oak trees and lightning on which that etymology is based).

stake < *s-teg- vs. *teg- > “thatch”, Punjabi ਠੱਗ [tʰag] “rogue, cheat”

stick, sting < *s-teig vs. *teig > “thistle”, Persian تیز [ti:z]

thunder, Persian تندر [tondaɾ] < *tenh₂- [tenɐ̥] vs. *s-tenh₂- [stenɐ] > Ancient and Modern Greek στενάζω [stenázo] “groan”

In shove < *s-keubʰ- vs. *ks(e)ubʰ- > Persian آشوب [a:ʃub] “chaos” there is metathesis of the *s- prefix with the stem-initial *k.

Satemization

By “satemization” (the lenition of pre-velar stops), postalveolar and alveolar affricates and fricatives arose in some daughter languages, notably in the so-called “satem” branches of Indo-European: Baltic, Slavic, Iranian, Indic, and Armenian. The term “satem” comes from the Avestan word for “hundred”, 𐬯𐬀𐬙𐬆𐬨 satəm, in which Proto-Indo-European *ḱ developed into Avestan [s], and is used in contradistinction to the so-called “centum” branches (Italic, Celtic, Greek and Germanic), in which Proto-Indo-European *ḱ was inherited as a velar consonant.

| Proto-Indo-European | Modern “satem” languages | |||||

| *ḱ [k̟ʲʰ] | > | *[cç] | > | [tʃ] | > | [ʃ] or [ɕ] |

| ∨ | ∨ | |||||

|

|

[ts] | > | [s] | |||

For example:

*ḱr̥-n- [k̟ʲr̩n] “horn” > Latin cornū [kornu:] vs. Sanskrit शृङ्ग [ʃɹ̩ŋgʌ], Lithuanian širšė [ʃirʃe], Latvian sirsenis, Persian سرنا [sornʌ], Armenian սար [sɑɹ]

*ḱel- [k̟ʲel] “hall” > Latin cella [kel:a] vs. Sanskrit शाला [ʃa:la]

*ḱónk-e- “hang” > Latin cunctor

[kuŋktor]

vs. Sanskrit शङ्क [ʃʌŋkʌ] “doubt”

*ḱh₂s-en- [kɐsən] “hare” > Proto-Italic *kasnos > Latin cānus [ka:nus] vs. Sanskrit शश [ɕʌɕʌ]

*déḱm̩-t “ten” > Latin decem [dekem] vs. Lithuanian dešimt, Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian deset

| Proto-Indo-European | Modern “satem” languages | |||||

| *ǵ [g̟ʲ] | > | *[ɟʝ] | > | [dʒ] | > | [ʒ] |

| ∨ | ∨ | |||||

| [dz] | > | [z] | ||||

For example:

*ǵr̥h₂nó- [grɐno] > Latin granum, Sanskrit जीर्ण jiirna [dʒirnʌ], Lithuanian žirnis, Latvian zirni “peas”

*ǵnéh₃- [g̟nəŏ] “know” > Ancient Greek γνώση gnose, Urdu جاننا [dʒʌ:nʌ:], Armenian ճանաչել [tʃˉɑnɑtʃʰel], Lithuanian žinau, Latvian zināt, Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian znam, Balochi زان [zʌn]

*ǵʰelh₃- [g̟ʲʱelŏ] “gold, yellow” > Lithuanian geltonas “yellow” vs. Lithuanian žalias “green”, Latvian zelts, zaļš, Bosnian zelena, Persian زرد [zærd]

In *gʷelh₁- [gwele̥] “kill, quell”, satemization is not expected because *gʷ is not fronted; hence Lithuanian įgelti “to sting” is as expected. Nevertheless, Latvian iedzelt “to sting”, Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian žaoka “stinger, barb” and Ukrainian жаль [ʒalʲ] “sorrow” show evidence of velar softening.

Fricatives arising via Grimm's Law

In Germanic languages including English, a different pattern of lenitions, formulated as part of Grimm's law, gave rise to other fricatives: *p > [f], *t > [θ], *ḱ and *k > [x] > [h]. For example:

Fricatives deriving from lenitions other than Grimm's Law:

*p > Proto-Celtic [ɸ], subsequently lost in modern Celtic languages; e.g. *polh₁-uo [polwo] > fallow, Proto-Celtic *ɸlētos > Irish liath.

*d > [ð]; e.g. *déḱm̩‑ “ten” > Albanian dhjetë, Modern Greek δέκα [ðékɐ].

*bʰ and *dʰ > [f] in Latin, e.g. *bʰuh₂ [bʱuɐ̆] > fuī > Spanish fui; *dʰwor‑ > Latin foris; *dʰuh₂-mos‑; > Latin fumos “smoke”.

... and many more, specific to their group of languages.

*r. The reflexes of *r are rather varied across the Indo-European daughter languages, including trills [r] and [ʀ], tap [ɾ], and frictionless continuant [ɹ]. In several examples of sound change in modern European languages, changes from [r] to [ɹ] or [ʀ] have been observed. For example, older English phoneticians describe [r], which persists in some modern dialects (e.g. Scottish English), though [ɹ] is now far more common. Likewise, Latin phoneticians describe alveolar [r], which persists in most Romance languages; the development of [ʀ] and subsequently [ʁ] in modern French is more recent, and is regional (albeit now standard), being a Northern French development. Similarly, the development from [r] to [ʀ] is historically documented in German and is specific to certain dialects. In view of such evidence, it is generally thought that [r] is the older pronunciation, and therefore Proto-Indo-European *r was probably alveolar, i.e. [r] or [ɾ].

In many living languages, [r] and [ɾ] are not contrastive (typically), but reflect variation in duration, i.e. a very short duration allowing only time for 1 momentary contact of the tongue tip against the alveolar ridge is a tap [ɾ], whereas if the consonant is longer and more sustained, an airflow supporting an oscillatory series of contacts is a trill, [r], which might more narrowly be transcibed [ɾɾɾ...]. In between the repeated tongue-contacts made during a trill, very short transitional vowels may be heard. When these are of a front quality, e.g. [ɾɪ̆ɾɪ̆ɾɪ̆...], a palatalized or "clear" trill is produced, which might less narrowly be transcribed simply as [rʲ]: Indic languages provide many examples of "clear" [r̩ʲ], e.g. *tr̥h₂- [tr̩ħa] > Sanskrit तिरस् tiras; Sanskrit तृण trnam > Bengali তৃণ trino “thorn”. Similarly, a velarized or dark trill [rˠ] has close back vocoids in between the taps, so might more narrowly be transcribed as [ɾɤ̆ɾɤ̆ɾɤ̆...]. Where the transitional vocoids are neither front nor back, but mid-central, a narrow transcription could be [ɾə̆ɾə̆ɾə̆...], though this would normally be transcribed as simply [r], a trill that is neither palatalized nor velarized.

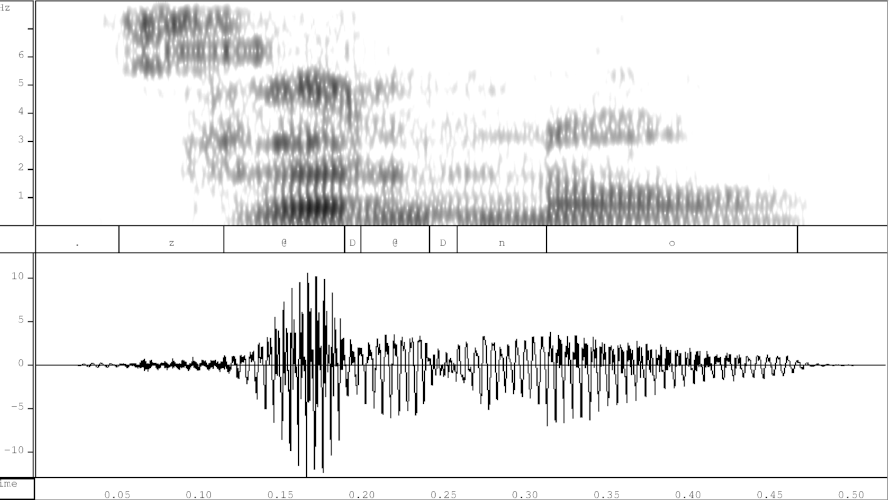

Such transitional vocoids help to explain at least some instances of apparent metathesis of Vowel+[r] ↔ [r]+Vowel, as in e.g. PIE *ǵr̥h₂nó- [g̟ʲrɐno] = [g̟ʲɾə̆ɾə̆ɾə̆...no] ~ [g̟ʲə̆ɾə̆ɾə̆ɾə̆...no] > [zə̆ɾə̆ɾə̆ɾə̆...no], Czech zrno [zɘrno]. In the labelled spectrogram and waveform of zrno (a trill consisting of two taps with a short intermediate vocoid, i.e. more narrowly [zɘɾɘ̆ɾno]), the vocoid portions are labelled as "@" and the tap closures are labelled in ASCII as "D". During the tap closures, the amplitude of the waveform is reduced as the egress of air (and sound) from the mouth is attenuated.

An under-articulated tap [ɾ̞], in which the tongue-tip approaches the alveolar ridge but does not actually make contact with it, produces an approximant [ɹ].

In summary, some common paths of development due to these dimensions of phonetic similarity are:

| Trill | Tap | Approximant | |||

| Alveolar | *r [r] | > | [ɾ] | > | [ɹ] |

| ∨ | |||||

| Uvular | [ʀ] |

As sociolinguistic variation between these various consonants is quite common, cross-linguistically, the simulations in the Audio Etymological Dictionary include trills, taps and approximants, mostly depending on the particular reflexes in later languages that are used in the simulations. (Of course, the existence of any particular type of rhotic sound in my simulations of Proto-Indo-European doesn't prove anything at all about the actual pronunciation in the distant past!)

Examples simulated here with trills:

h₂erh₁-mos [armos], earlier [ħer:mos] > Modern Greek αρμός [armos]. Cf. Sanskrit ईर्म [iɾmɐ], with a tap.

*bʰerǵʰ-os > Proto-Germanic *berga-, Balochi برز ئه [borzɐ] “height”.

*ǵr̥h₂nó- [g̟ʲrɐno] “corn” > Latin granum, Czech zrno [zɘrno]

*ph₂-tḗr [pɑté:r] “father” > Persian پدر pedar

*priH-eh₂- [pʰri:ɐ:] “friend” > Bosnian prijatelj

*ḱerd [k̟ʲerd] “heart” > Hindi हृदय hrday, with an alveolar approximant

*mrk [mr̩k] “morn” > Bosnian mrak

*smer [smer] “mourn” > Sanskrit स्मरति smarati

*mŕ-to- [mr̩to] “murder” > Persian مردن mordan,

with an alveolar approximant

*gʷerh₂-nu- [gwerənu] “heavy” (cognate with quern) > Balochi گران graan. Cf. Ancient Greek βάρος [baɾos], with a tap.

Examples simulated here with taps:

*h₂eǵ-ro-s [ɐg̟ʲɾós] “acre” (field), closely based on a recording of Ancient Greek αγρός [ɐgɾós] > (Modern Spoken) Sanskrit अज्र [ɐʤɾɐ]

*h₃bʰruH-s [ŏ̥bʱɾuəs] “brow” > Ancient Greek ὀφρῦς ophrus, Urdu ابرو abru (pronounced with an approximant in this example)

*gerbʰ‑ [geɾə̆bʱ] “carve” > Albanian gërvisht [gəɹviʃt] “scratch” (with an approximant)

Examples with approximants i.e. [ɹ] or [ɻ] are abundant in the English examples, and are also found in other branches of Indo-European, as mentioned in some of the examples above.

The phonological similarity of [r] and [l] is seen in sound changes such as *pór-e‑ “fare” > Persian پل pul “bridge”; and in the opposite direction e.g. *ḱel-to- “cold” > Persian سرد sard, *plth₂- [pl̩tɐ] “field” > Sanskrit पृथु prthu, *pleḱ-t‑ “flax” > Sanskrit प्रश्न prashna, *plh₁-nó- [pl̩n —] “full” > Persian پر pur, Sanskrit पृणाति prnaati; *melh₁‑ “meal” > Sanskrit मृद् mrd; and *leuk‑ [lɘʊk] “light” > Balochi روچ roch “day”.

Examples of syllabic [r]

*ǵr̥h₂nó- “corn, grain” > Czech zrno

*mr̥ǵʰ-u‑ > American English mirth [mɹ̩θ]

*mŕ̥-to- [mr̩to] > American English murder [mɹ̩dɚ]

*mr̥k [mr̩k] “morn” > Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, Serbian and Slovenian mrak (with non-syllabic [r])

*s-pr̥gʰ‑ “spring” (derived from *s-pérgʰ- [spɘrgʱ]) > Pashto [sprəʒ] (with non-syllabic [r])

*tr̥s-no‑, *tr̥s-tu “thirst” > Persian تشنگی teshne, American English thirst [θɚst] ~ [θɹ̩st]

*tr̥no [tr̩nõ] “thorn” > Sanskrit तृण trnam, Bosnian trn

*tr̥h₂- [tr̩ħa] (derived from *terh₂‑ “through”) > Sanskrit तिरस् tiras

*wr̥h₁t- [wɹ̩e̥tʰ] “word” > American English word [wɹ̩d], Sanskrit and Hindi व्रत vrat (with non-syllabic [ɹ])

*wr̥ǵ- [wɹ̩g̟̊ʲ] “work” > Proto-Hellenic and Doric Greek ϝέργον wergon, Persian ورز varz, American English work [wɹ̩k]

*l.

Across the modern Indo-European languages, varieties of [l] occur with a range of secondary articulations from “clear” (palatalized) to “dark”. In some languages such a distinction is phonemic (e.g. in Russian, Gaelic); in others it may be positional (e.g. English “leaf” vs. “feel”). The Audio Etymological Lexicon exemplifies the following varieties of secondary articulation of [l]:Examples with “clear” [l]

Sanskrit अंगुली anguli “finger” (ankle), Ancient Greek ἀγκύλος angulos, Lithuanian obuolys “apple”, Persian بالش balesh “pillow, cushion”, Bosnian brbljati “bleat”, Ancient Greek κύκλος küklos (cycle), Modern Greek ωλένη oleni “ulna”, Latin ulna, Armenian այլ ayl “also” (else), Sanskrit पलित palita “grey” (fallow), Persian پل pul “bridge”, Bosnian zelena “green” (gold), Sanskrit शाला shaala “hall”, Nepali कपाल kapaal “skull”, Polish lepić “mould” (leave), Hindi स्थल sthal “dry land”, Pashto اوبدل obdal “weave”. Notice that in several of these examples, a postvocalic or even final [l] may be clear, contrary to their quality in English phonetics.

Examples with “dark” [l]

Macedonian jabolko, Latvian blēt “bleat”, Ukrainian Долина Dolyna “Dale”, Latvian olekts “elbow”, Ukrainian плавати plavati “float”, Bosnian gladak “smooth”, Bosnian glumiti, “act, pretend” (glee), Bosnian ležati “lie down” and lagati “lie”, Urdu ملنا malna “rubbing” (meal), Siraiki mẽghla “mist”, and Latvian sāls “salt”.

Note that it is not always the case that pre-vocalic [l] is clear; for example, in Latvian olekts it's somewhat dark. Nor is it always the case that postvocalic [l] is dark; for example, in Armenian այլ ayl, Persian پل pul, and Pashto اوبدل obdal “weave”, it's quite clear. Nor is it the case that the secondary articulation of an [l] in different cognates will be clear or dark in all the daughter languages, consistently; for example, [l] is clear in Lithuanian obuolys “apple” but is dark in the Macedonian reflex jabolko, possibly because of their different vocalic contexts and/or syllable positions. Similarly, Bosnian brbljati “bleat” has a clear [l] whereas in its Latvian cognate blēt, [l] is dark; Hindi स्थल sthal has a clear [l] whereas its English cognate stall in many dialects has a dark [l]; and though Ukrainian плавати plavati “float” has a relatively dark [l], the closely-related and otherwise almost identical Slovenian form plavati has a fairly clear [l]. At first pass it therefore looks as if it may not be possible to generalize about whether Proto-Indo-European *l was inherently clear or dark.

Examples of syllabic [l̩]

*pl̥th₂- [pl̩tɐ] “field” > Sanskrit पृथु prthu

*ml̥h₂-téh₂ [ml̩:teħ] “mould” > Sanskrit and Hindi मृदा mrda

*sl̥h₁‑ (derived from *selh₁‑) “sell” > Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian slati “to send”, with nonsyllabic [l]

*sóh₂wl̥ [sɒʊɫ] “sun” > Sanskrit स्वर् svar

*wĺ̥kʷ- [wl̩kʷ] “wolf” > Slovak vlk, Sanskrit वृक vrka

[l] vocalization

In a number of Indo-European languages, Proto-Indo-European *l vocalized

to become a high, back, rounded vowel [u] or [o], e.g.:

*h₂ebol [ħɑboɫ] > South Slavic (e.g. Macedonian) jabolko > Bosnian jabuka

*gʷelh₁- [gwele̥] “kill” > Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian žaoka

*wĺ̥kʷ- [wl̩kʷ] “wolf” > Bosnian vuk (cf. Slovak vlk, which retains unvocalized syllabic [l])

*wĺ̥h₁-neh₂- [wl̩naħ] “wool” > Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian vuna

A close phonological relationship between [l] and [n] is seen in variation in the pronunciation of the word for “sun”, *séh₂un‑ [sɑʊɵn] ~ *séh₂ul‑ [sɐʊɫ]. Historically, also, [l] and [n] are seen to be related in etymologies such as Latin alter < *h₂eltero‑, variant of *h₂entero‑.

| Previous: Stops: Places of articulation | Next: Vocoids

and “laryngeals” |