The three so-called laryngeals of Proto-Indo-European, conventionally transcribed as *h₁, *h₂, and *h₃ (sometimes as *H₁, *H₂, and *H₃ or *ə₁, *ə₂, and *ə₃), are abstract phonological units whose existence and nature are mostly inferred from their effects on neighboring vowels and consonants. Their exact pronunciation is unknown (so the term “laryngeal” should not be understood literally as a definite phonetic description), but some hints can be deduced from their various manifestations in daughter languages. Various possibilities — all logically possible but inconclusively different — have been argued for by different linguists. Here, I attempt to provide an overview of a consensus opinion and to survey the various pieces of evidence that have been adduced in discussions of the nature of laryngeals, giving links to the specific audio recordings and simulations that I have developed in my Audio Etymological Dictionary (http://www.ancientsounds.net/) together with examples from other languages, such as Arabic, which may serve to illustrate possible parallels. (This webpage has grown and grown; if you want the "executive summary", jump to the conclusions.)

As usual in linguistics, “>” is shorthand for “developed into”, “<” is shorthand for “developed from”, to which I add “≈” as shorthand for “was pronounced more or less the same as” and “≳” to mean “developed with hardly any change in pronunciation into”. I don't (yet) give simulations of the sound changes here, but many of them can be found at http://www.ancientsounds.net/. But there are here many hyperlinks to audio recordings or synthetic simulations of the pronunciations in question, so click to listen to them; they're best heard through headphones.

Characteristics of laryngeals:

1) Laryngeals can serve as syllable nuclei, in which case they could have been pronounced as vowels. Ancient Greek provides many examples of this type, e.g.

*h₁roudʰ- [hɾoʊdʱ] “red” > Ancient Greek ἐρυθ(ρός) [erutʰrós]; *h₁rebʰ- [hrebʱ] “rib” > Ancient Greek ἐρέφω [erépʰo] “to roof”

*h₂stér [ħɐ̥stér] “star” > Ancient Greek

ἀστήρ [astér]

*h₃bʰruH-s [ŏ̥bʱɾʉ:s] “brow” > Ancient Greek ὀφρῦς [opʰrŷ:s]

The Modern Greek versions of such words provide primary audio data concerning their Ancient Greek pronunciation.

2) Their three distinct outcomes in Ancient Greek, such as those just cited, give evidence that there were three laryngeals. (It might be equivalent to argue that there was just one laryngeal consonant *h in combination with three short vowels *e, *a and *o, i.e. that *h₁ = *he or *eh, *h₂ = *ha or *ah, and *h₃ = *ho or *oh, but other evidence weighs against that.)

3) They modify the quantity and quality (“coloring”) of the nuclear vowel /e/. In particular:

Their lengthening effect when they follow vowels, but not when they precede vowels, is similar to the differential phonological behaviour of glides such as /j/ and /w/ after vs. before vowels. Cross-linguistically, in “rising” diphthongs (e.g. /j/+Vowel or /w/+Vowel), the resulting diphthong is short, whereas “falling” diphthongs such as Vowel+/j/ or Vowel+/w/ often (typically) behave metrically like long vowels, and may make a syllable metrically “heavy”.

On the strength of this kind of evidence in particular, Reynolds et al. (2000) argued that the three laryngeals were in fact three non-syllabic vocoids /e̯/, /a̯/ and /o̯/, and that their various consonantal reflexes were due to devoicing of those vowels. As the laryngeals in their “vocalic” realizations were unstressed, Rasmussen (1983) proposes they were somewhat centralized i.e. [ə], [ɐ], [ɵ]. In the present version of the IPA alphabet, [ɘ] is perhaps preferable to [ə], as [ɘ] is mid-central but close to [e]; for the other two laryngeals, [ɑ̆] and [ŏ] also seem appropriate to use in some contexts, as will be seen from the examples presented below.

Consonantal characteristics

4) Position in syllables: Their position in syllables provides evidence that they were less sonorous than sonorant consonants liquids and nasals, but more sonorous than stops, which suggests they could have been fricatives.

5) “Laryngeal aspiration”: In Indo-Iranian they sometimes survive in the form of aspiration of a preceding consonant.

6) In some cases of “laryngeal aspiration”, *h₂ and sometimes *h₁ cause the devoicing of a preceding voiced consonant.

Conversely, *h₃ is often taken to have been voiced, based on the evidence of the perfect form *pi-bh₃- from the root *peh₃ “drink”, in which the medial p- becomes voiced when the following vowel is dropped bringing it into contact with h₃- and thus becoming voiced by assimilation. This would make phonological sense if *h₃- were itself voiced, but otherwise would be a rather arbitrary and puzzling change. I argue below that if *h₃ were a voiced pharyngeal approximant, the retraction of the tongue root that would be needed for its articulation explains its behaviour in causing lip-rounding.

7) Relatedly, in Indo-Iranian, Ancient Greek, Armenian and Albanian there are occasional examples of their surviving as voiceless fricatives such as [ħ], [h], or [x].

Orthographic evidence

8) In Cuneiform Hittite and Luwian, *h₂ and sometimes *h₃ are written with letters that were originally (in Babylonian etc.) used for a voiceless fricative ḫ or ḫa, believed to have been pronounced with a velar or possibly uvular fricative [x] or [χ], e.g. Hittite ḫants “front, face” < *h₂ent- “face”; Luwian ḫawi- < *h₃éu-i-s [ħʷo:is] “sheep, ewe”.

In view of the evidence presented above, it is now generally thought that the laryngeals were, at an earlier stage, pronounced as guttural consonants (a traditional term that covers laryngeal, glottal, uvular, and retracted velar consonants, advocated by McCarthy 1994), which developed into vocoids or modified the quantity and/or quality of neighbouring vowels at at a later stage. A current textbook, Fortson (2010: 64), states that

one fairly widespread view has it that *h₁ was a simple h or a glottal stop [ʔ], *h₂ a voiceless pharyngeal fricative [ħ] … and *h₃ a voiced pharyngeal fricative [ʕ̶] …

These seem phonetically reasonable proposals:

*h₁. Postvocalic [h] often has the effect of perceptually lengthening a preceding vowel without otherwise changing its quality, which is a characteristic of postvocalic *h₁. For example, in the history of English, Old English niht [nixt] "night" weakened the [x] to [h], giving Middle English [niht]. This [h] is essentially a whispered version of the preceding vowel, i.e. [nii̥t], i.e. a close, front vowel that begins voiced but devoices in its later part. Subsequently, the voicing of the earlier part of that vowel extended throughout the vowel, so that the whispered part became voiced too, which gives a long (voiced) vowel [ni:t], even though its Old English ancestor was a short vowel. That long vowel was then subject to the series of changes termed the "Great Vowel Shift", which affected only Middle English long vowels, so that it is now pronounced [naɪt]. The derivation of *h₁upo “up”, from an earlier *supo (cf. Latin super) makes sense if *h₁ was [h], because s > h is a cross-linguistically common sound change.

Contrary to the second of Fortson's suggestions, I note that postvocalic [ʔ] has the effect of cutting a vowel short. For example, glottalized consonants in Cantonese only occur with short vowels and level tones. In some varieties of English, postvocalic glottal closure is a feature of following voiceless consonants, that voicelessness being cued primarily by the shorter duration of the preceding vowel. Vowels before glottalized voiceless consonants are significantly shorter in duration compared to their durations before voiced consonants (“pre-fortis clipping”) or in open syllables. In view of such parallels, we would expect postvocalic [ʔ] (if it occurred in Proto-Indo-European) to be a shortener of preceding vowels, not a lengthener. Therefore, the proposal that *h₁ was [h] seems more plausible than that it was a glottal stop [ʔ]. This does not disprove the possibility that it might have been a glottal stop, as those so-called "stops" are often pronounced just as creaky voice at the end of the vowel, which could be a long vowel. But cross-linguistically, it seems to be the case that postvocalic glottal stops are associated with vowel shortness rather than length. A more detailed typological survey would be useful.

*h₂.The voiceless pharyngeal fricative [ħ] has a low, back tongue position and is hardly different from a whispered [ɐ̥] or [ɑ̥], as heard in the coloring of *h₂ (or possibly or variably a voiceless uvular fricative [χ]).

*h₃. The lip-rounding effect of pharyngealization on neighbouring vowels is attested in living languages, such as in Swahili and some varieties of Arabic (see section 3f below). Cross-linguistically, voiced pharyngeal fricatives are rather rare, whereas voiced pharyngeal approximants are far more common, so contrary to Fortson's suggestion that *h₃ was a voiced pharyngeal fricative [ʕ̶], I think it more likely that it could have been a voiced pharyngeal approximant (glide), as the examples presented below (such as *h₃éu-i-s [ʕo:is] “ewe”) shall illustrate.

If or when laryngeals were obstruents, a path of development towards a vowel could naturally progress via a devoiced/whispered vocoid, which can be modelled by a path of interpolation between full vowels and silence or [h]. As may be heard in the examples below, the audio simulations of Proto-Indo-European words presented here instantiate the hypotheses that:

The methodology for generating continua of changing sounds means that we

do not need to take a fixed, exclusive view of the phonetic nature of

laryngeals, as different qualities are generated at different points on

each continuum: voiced vowels in some reflexes, perhaps voiceless vowels

at an earlier stage (later Proto-Indo-European), and “guttural” obstruents

at an even earlier stage. For that reason, a range of possible phonetic

qualities of laryngeals can be heard in the simulations at http://www.ancientsounds.net/.

I now expand on the above eight characteristics of laryngeals with

examples and some discussion.

This is found in two positions in the word: (a) word-initially, before a consonant, and (b) word-medially, between two consonants.

(a) Initial *h₁ + Consonant

*h₁néun [e̥néun] “nine” > Ancient and Modern Greek ἐννέα [en:éa].

*h₁roudʰ- [hɾoʊdʱ] “red” > Ancient Greek ἐρυθ(ρός) [erutʰrós], Latvian [h]ruds.

*h₁reug- [ɘ̥ɻɛʊg] “reek, belch” > Ancient Greek ἐρεύγομαι ereúg-omai.

*h₁rebʰ- [hrebʱ] “rib” > Ancient Greek ἐρέφω [erépʰo:] “to roof”.

*h₁lengwʰ-to- [e̥lʲɐŋgʷʰ—] “light” (in weight) > Ancient Greek ἐλαχύς elakhüs.

(b) Non-initial syllabic *h₁

*bʰerh₁ǵ- [bʱeɾɘg̟ʲ] “bright” > Lithuanian brėkšta “to dawn”.

*dʰh₁- “do”. Evidence for *h₁ = [e] comes from the zero-grade form *dʰh₁-tó-s > Ancient Greek θετός [tʰetós] “placed” > Modern Greek [θetós] “adopted”.

*gʷelh₁- [gwele̥] “quell, kill” > Ancient Greek βέλεμνον [bélemnon], “javelin, dart”, cf. English belemnite.

*ǵenh₁- [g̟ʲenə] “kin” > *ǵn̥h₁tós > Ancient Greek suffix -γνητός -gnētós “-born”; *ǵénh₁-tōr > Ancient Greek γενέτωρ genétōr, γενέτης [genétes] “parent”, γενέτα [genéta] “birth”, Modern Greek γενέτειρα [ʝenétira] “birthplace”.

*wl̥h́₁-neh₂- [wl̩énaħ] “wool” > Proto-Hellenic *wlḗnos > Ancient Greek λῆνος [le:nos].

*sph̥₁-ro- [spɘro] > “spare”. In theory its development into Ancient Greek σπαρνός [spaɾnós] (audio interpolated from Modern Greek σπανός [spanós]) presents a potential counterexample as its vowel might suggest *h₂ (because *h₂ > [ɐ], as illustrated below) rather than *h₁ (which would be expected to develop into [ɘ]). Long [e:] reflexes of *eh₁- in the root *speh₁- are heard in Latin spēs, Latvian spẽt, Lithuanian spėti, and Slovenian speti.

*smH-oro- (Kroonen), *sm̩H- (Ringe) “summer” could be *sm̩h₁- [sɘmħɐ̥] > Sanskrit समा samaa

In *polh₁-tos [polɪtos] “fallow, grey” it's somewhat unclear why a medial h₁ laryngeal would vocalize in this environment, because a fricative would be less sonorous than the preceding sonorant [l] (albeit more sonorous than the following stop [t]); perhaps there was a morphophonemic constraint against consonant clusters as large as in *polhtos, or perhaps the laryngeal was not in fact a fricative (Reynolds et al. 2000). Evidence for a vowel in this position in the stem *pelh₁- is seen in Sanskrit पलित [palɪtá], Ancient Greek πελιτνός [pelɪtnós], and Latvian pelēks. Its quality in these examples as [ɪ] or [e] is evidence that it was *h₁, not *h₂ or *h₃ (but Albanian plak “old man” < Proto-Indo-European *pl̥H-ko- could suggest *pelh₂- not *pelh₁-; and Latvian pelēks may be pronounced [pʰɐlɐks], as if from *pelh₂-).

(c) Initial *h₂C

*h₂melǵ- [ɐ̥melg̟ʲ] “milk” > Ancient

Greek ἀμέλγω [amelgo:]. Compare the simulation

of *h₂melǵ- [ɐ̥melg̟ʲ] with the pronunciation

of Egyptian Arabic حَمَلَ ḥamala [ħamælæ] and South Levantine Arabic

حَمَلَ [ħamal]. (The Arabic words

presented on this page are entirely unrelated to Proto-Indo-European and thus have quite different meanings. They are given here

simply because of their similarity in sound to what is proposed here as

the possible pronunciation of Proto-Indo-European words under discussion.)

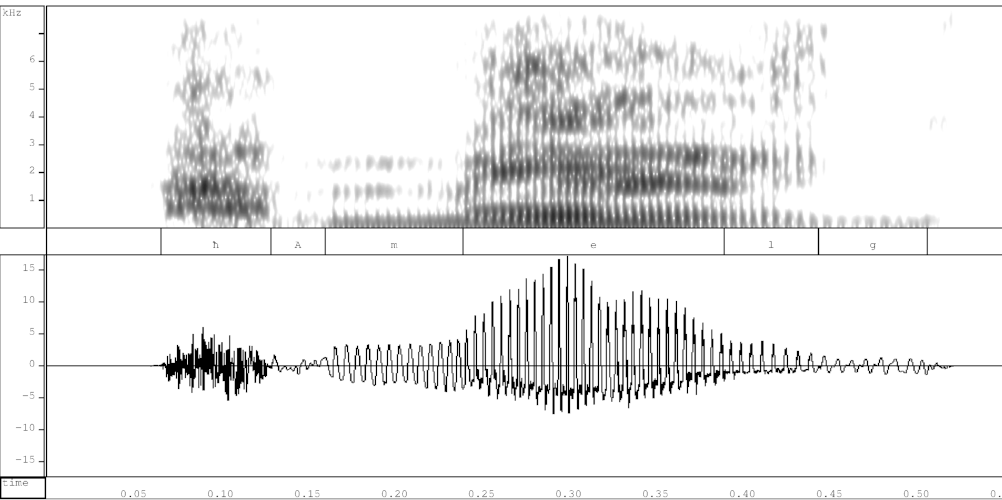

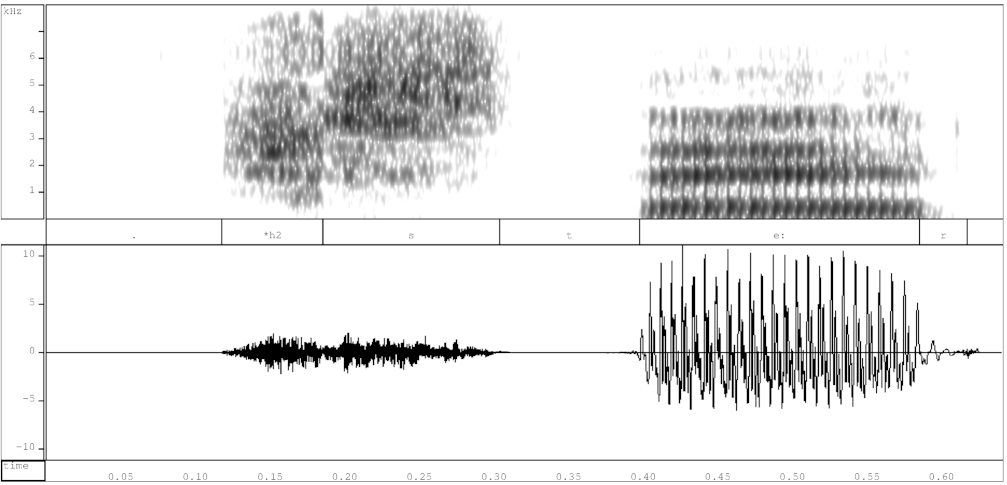

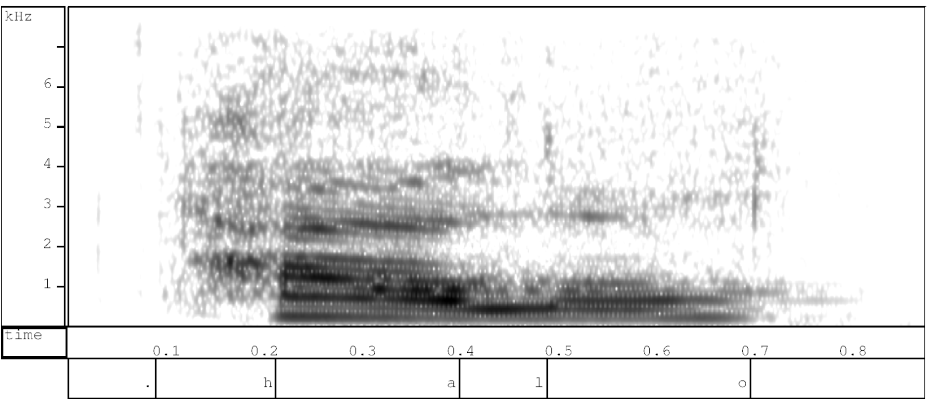

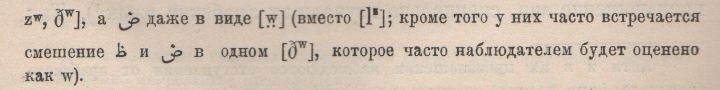

In both of the spectrograms below, the second and third formants of the initial [ħ] and the following vowel [a] can be seen to be flat and relatively unchanging. The first formant frequency of [ħ] is hard to discern in these plots, but is somewhat higher than that of the following vowel, indicating that the tongue root is more retracted i.e. the pharynx is somewhat more constricted for [ħ] than for the vowel [a], the quality of which is not especially back. The initial [ħ] is however voiceless and has considerable frication, so that the waveforms of [ħ] and [a] are very different. In the simulation of *h₂melǵ- (upper spectrogram), it can be seen that the vowel [ɐ̥] is also voiceless, making that portion of the signal look like a fainter version of the [ħ] that precedes it.

|

| Above: spectrogram and waveform of simulated *h₂melǵ; below, spectrogram and waveform of South Levantine Arabic ħamal. |

|

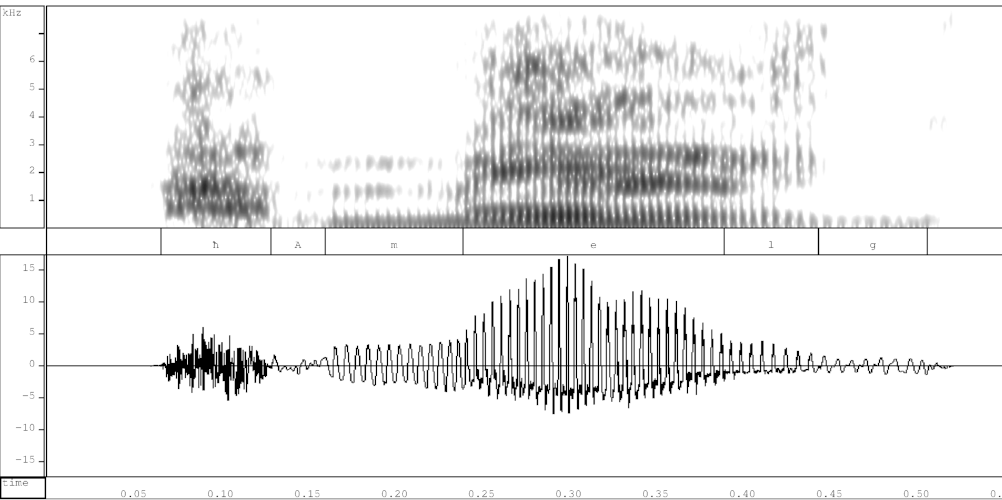

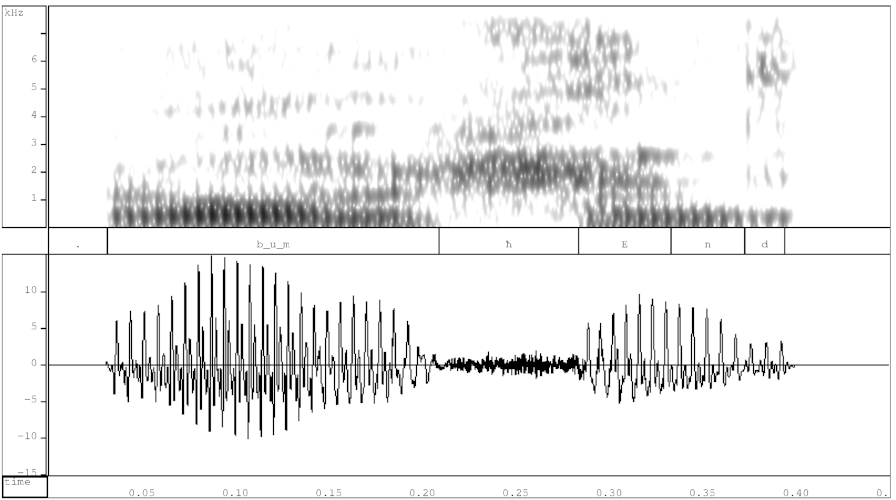

*h₂noḱ- [ɐ̥nok̟ʲ] ~ [ħnok̟ʲ] “enough” > Ancient Greek ἀνάγκη [anáŋke:]; *h₂n̥ḱ > *hans- > Armenian հասնել [hasnel] (see below for discussion of the retention of this initial [h]). The following figure compares the spectrogram and waveform of the simulation of *h₂noḱ- (upper panel) to the first two syllables of Emirati Arabic حَنَّكَتك ḥannak(atk) [ħan:akætk] (lower panel).

|

| Above: spectrogram and waveform of simulated *h₂noḱ- (with a voiced final consonant, in fact). Below: spectrogram and waveform of Emirati Arabic حَنَّكَتك ḥannakatk. |

|

*h₂roh₁(ǵ)-eh₂- [ɐ̥ɾo:gɐ:] “reck-” > Ancient Greek ἀρωγή [aro:ge] “aid”, related to ἀρήγω arḗgō “I help”. (Beekes proposes an alternative derivation, from ὀρέγω [orégo:] “I reach out”, from Proto-Indo-European *h₃rēǵ‑ [ŏre:g̟ʲ] “straight”, with initial *h₃.)

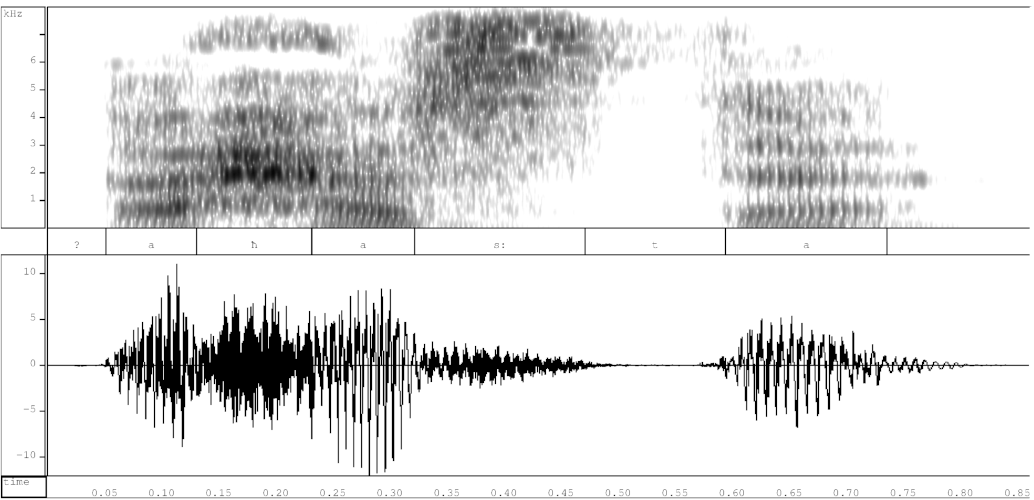

*h₂stér [ħstér]

“star” > Ancient Greek ἀστήρ [asté:r], Northern

(Kurmanji) Kurdish [astirə], Armenian աստղ [ɐstɐʁ]. Purely for the pronunciation, compare Emirati Arabic أَحَسْتَ [ʔæħæs:tæ].

|

| Above: spectrogram and waveform of simulated *h₂stér [ħɐ̥stér]. Below: spectrogram and waveform of Emirati Arabic أَحَسْتَ [ʔæħæs:tæ]. |

|

*h₂sous- [ɑ̥sous], [ħsous] “sear”. Evidence for the initial *h₂ coming to being pronounced as [a] is provided by the development from the zero-grade form *h₂sús-ye- > Proto-Hellenic *ahúhyō > *ahuo > Ancient Greek αὔω hauo (no suitable recordings available). For evidence of the initial *h₂ pronounced as a voiceless guttural fricative, see the discussion of *h₂e-h₂s- [ħaχs] “ash” in section 7, below.

*h₂wés- [ħwes] “was, were”. This simulation was a hybrid of Latin aves [awe:s] “bird” (chosen purely for its pronunciation; there is no semantic connection to “was/were”) and [ʍɛs], edited from a recording of English whe(t)s(tone). Evidence for the nature of the initial *h₂ comes from the development of *h₂wés- into Proto-Hellenic *áwesa > Ancient Greek ἄεσα [áesa] “I stayed/spent the night/slept”.

*h₂wég-s- [ħwegs] “wax” > *awéxein > Ancient Greek ἀέξειν aéxein. Since I have no recording of ἀέξειν, we rely on the related form *h₂éug- [hɑug] “eke” (discussed below) for audio illustration of the initial *h₂-.

*h₂weh₁nt- [ɐwe:nt], earlier [ħwe:nt] “wind” > Proto-Hellenic *áwēmi > Classical Greek ἄϝημι > ἄημι [áe:mi].

*h₂yuh₁n-ḱós [ɐju:nk̟ʲǝs] “young”, formed from the zero grade of *h₂óy- [ɔi] “lifetime”. The oblique form *h₂y-wé- [ɐiwe] > Proto-Hellenic *aiwei > Ancient Greek αἰεί [aĭé̝ĭ] “always”.

*bʰuh₂ [bʱuɐ], earlier [bʱuɐ̥], [bʱuħ] “be”. *bʰúh₂-t > Proto-Italic *fūai > Latin fuī “I was”. *bʰúh₂-tis > Proto-Albanian *bwātā > Albanian botë “world, that which is”. *bʰuh₂-ti-ḱos > Ancient Greek φυσικός [pʰʉsikós], whence English physical.

*ǵh̥₂r- [g̟ɐɹ̝] “care” > Latin garriō, Doric Greek γᾶρυς [gærus] (here exemplified by a proxy from Lithuanian). Purely for the pronunciation, compare Egyptian Arabic جحر [ʤɑħrə].

*ǵr̥h₂nó- [g̟ʲrɐno] “corn” > Latin grānum. Contrast this vocalic pronunciation with what a consonantal realization might sound like, as in the similar-sounding Syrian Arabic word جَرْح jarḥ [ʤɑɾə̆ħ].

*dh₂i-tí- [dɐití] “tide”, a form of *dh₂i- [dɐi] > Sanskrit दैत्य [dɐitjə]; *dh₂i-mon [dɐimon] “time” ≳ Ancient Greek δαίμων [daímo:n].

*dʰugh₂tḗr [dʱugɐté:r], earlier [dʱugħté:ɾ] “daughter” > Ancient Greek θυγατέρα [tʰugaté:ra].

*ḱh₂s-en- [kʰasən] “hare”, *ḱh₂s- “grey” > Proto-Italic *kasnos > *kahnos > Latin cānus “white”.

*kh₂péh₁- [kapé:] “have”. *kh₂p- [kap] > Albanian kap “grab, catch”, Ancient Greek κάπτω [kapto:] “gulp”, Latin cape, capiō, from which comes English capture.

*kh₂p-ut-

[kaput]

“head” > Latin caput.

*nh̥₂-s-eh₂- [nɐsɐ̥:]; *nh₂s- [nɐs] “nose” > Latin nāsus, Hindi नाक [nɐ:k], Romani nak.

*ph₂sth₂-o- “fast” > Armenian հաստ [hast].

*ph₂tḗr [pɑté:r], earlier [pħté:r] “father” > Latin pater, Ancient Greek πατήρ [pɐté:r]. Related to *peh₂- [peħ, peɐ̥] (see section 3b) “to protect, feed” + *-tḗr (agentive suffix) lit. “one who protects/feeds”.

*péth₂-r- [pétɐr], earlier [pétħr] “feather”. Evidence that the vowel of the second syllable was [ɐ] (and therefore can be reconstructed as *h₂) is given by Ancient Greek πέταλον péta-lon, πέταλος péta-los “leaf, petal” > Modern Greek πέταλο [pétalo] “horseshoe, petal”; Hittite pettar ‘wing, feather’ (Kloekhorst 2007: 762).

*pterh₂ [pterħ] “fern”. In view of the semantic connections between “wing”, “feather”, “leaf/petal” and “bird”, *pterh₂ [pterħ] and *péth₂-r- [pétɐr] seem to be closely connected. As *h₂ = [ɐ] is motivated in *péth₂-r- by Ancient Greek πέταλον péta-lon (Modern Greek πέταλο [pétalo]), and Hittite pettar, it seems also justified in the reconstruction of this word for “fern”.

*ph₂u- [pɐu] “few” > Latin paucus. Proto-Indo-Iranian *pu-trás, with loss of *h₂ (but NB aspiration of the initial [p]), is exemplified by Sanskrit/Hindi पुत्र [pʰutʰrə], Urdu پُوت [pu:t] “son” (without aspiration), cf. Sanskrit ब्रह्मपुत्र Brahmaputra, “son of Brahma”.

*pelth₂- [peltɐ] ~ [peltħ] “field”; *plth₂- [pl̩tɐ] “flat”. Etymological evidence for *h₂ > a in this word is slim, but Ancient Greek πλαταμών [platamo:n] “broad, flat area”, Proto-Hellenic *pləta-wia > Πλᾰ́ταιᾰ Plataia (literally) “Flat Country” are instances.

*prh₂-mó- [pʰrɐmo] “former”. The full form of this stem, *preh₂- [pʰreɐ], “first” > Hindi प्रथम [præɐ̆tʰʌm].

*gʷerh₂-nu- [gwerən—] “quern” > Persian گران [geɾɑn]. This word is connected to Proto-Indo-European *gʷéh₂rus [gwɐ:rus] ~ *gʷréh₂-us [gʷrɐ:us] (Proto-Hellenic *gʷarus > Ancient Greek βάρος [baros] “weight”; Proto-Italic *gʷraus > Latin gravis “heavy”) and Proto-Indo-European *gʷréh₂wō > Proto-Celtic *brawū > Scottish Gaelic brà “quern”.

*krouh₂- [kɾoʊħḁ] “raw”. Evidence concerning this *h₂ comes from the e-grade stem *kreuh₂- [kɾeʊħ] > Proto-Hellenic *krewa > Ancient Greek κρέας [kréas] “flesh”.

*sh₂-l-os [salos], genitive of *seh₂l-s “salt”. Evidence for [a] in the first syllable is abundant, e.g. Latvian sāls, Irish salann, Welsh halen, Latin, Portuguese, Spanish sal, Ancient Greek ἅλς [hals] > Modern Greek αλάτι [ɐlɐ́ti], Armenian աղ [ɐɬ].

Evidence for [a] in *steh₂‑ [steɐħ], [steḁ] > [sta:] ~ *sth₂- [sta] “to stand” comes from *sth₂-ti-, derived from *stéh₂-ti-, “stead” > Proto-Hellenic *státis > Ancient Greek στάσις [stásis], Germanic (e.g. Swedish) stad.

From the same root, *sth₂-énti [stɐnti] “stand” > Ukrainian стати [stɐ:ti], Croatian stati, Welsh gwastad. Sanskrit तिष्ठति tiṣṭhati [tɪʂʈʰɐti] and Persian ایستادن [istɑ:dæn] are consistent with this analysis but are inconclusive because all three laryngeals merged into [a] in Indo-Iranian.

*sth₂-bʰo- [stɐbʰo] “staff” > Lithuanian stãbas. Sanskrit स्तभ्नाति stabhnā́ti, स्तम्भ stambha and Persian ستبر [sĕtabr̩] “thick, stout” are inconclusive because in Indo-Iranian all three laryngeals developed into [a].

In *sth₂-dʰlo- [stɐdʱlo] “stall”, inconclusive evidence of *h₂ pronounced as [ɐ] comes from Sanskrit स्थला sthálā “platform, raised mound, arid/dry land” > Hindi स्थल [stʰɐl]. Ancient Greek στέλλω [stél:o:] and Modern Greek στέλνω [stélno:] might seem to point to *h₁, because of their [e] vowels, but the consensus is for *h₂ in this root because of the many other derived forms of *sth₂- in which the outcome is [a], not [e], as in the previous examples (stand, staff, stasis, stad, stãbas etc.). Likewise in *stéh₂-ur [stɐ:r] (from *stéh₂‑) ~ *sth₂-ur “steer(ing pole)” i.e. “a stand(ing thing)”, evidence for *h₂ being pronounced as [a] in the first syllable comes mainly from those other examples of words containing *sth₂-.

According to Kroonen's analysis, the *h₂'s in *ph₂sth₂-o- [pastao] “fast” are motivated by the derivation of this word from *ph₂ǵ-sth₂‑, a compound of *ph₂ǵ‑ “to fix” and *steh₂‑ [steɐħ] “to stand” (see section 3b). *ph₂ǵ‑ is also behind the stem of Latin pagus “region, countryside”, as in paganus “countrysider” (whence English pagan).

My simulation of *semh₂- [sɘmħɐ̥] “summer” is edited from a recording of Arabic سماحة [sɘmæħɐ̰], with the [æ] spliced out. Evidence of *h₂ pronounced as [a] in the second syllable comes from Armenian ամառ [ɑmɑr]. Additional but inconclusive evidence for the pronunciation of *h₂ as [ɑ:] comes from the Sanskrit form of this word, समा [samɑ:], and is suggested from the spelling of Old Irish samrad (the modern Irish pronunciation of samhradh has [ə] in the second syllable).

*terh₂-kʷe [terɐ̥kwe] “through”. *tr̥h₂-nts > Proto-Italic *trānts > Latin trāns. For the phonetics of *térh₂-, compare Algerian Arabic اقْتَرَحَ iqtaraḥa [ɪqˈtɐrɐħʌ] or Moroccan Arabic [ɪqˈtɐrɐħɐ] with Egyptian Arabic اقترح iqtaraḥ [ïqˈtˤɑrˤɑħ:], which shows “emphatic retraction” throughout the whole word.

*s-tenh₂- [stenɐ], a prefixed form of *tenh₂- [tenɐ̥], “thunder” > Ancient and Modern Greek στενάζω [stenazo:] “groan”.

(e) Initial syllabic *h₃ (e.g. h₃C, zero ablaut). I have simulated most of these with a devoiced onset; however, it seems quite possible and perhaps evern more likely that *h₃ was voiced, not voiceless. But cf. *h₃owis, which has voiceless reflexes.*h₃bʰruH-s [ŏ̥bʱɾʉ:s] “brow” > Ancient Greek ὀφρύς [ophrý:s], ὀφρῦς [ophrŷ:s]. The exact nature of the laryngeal in the second syllable is not known; I am inclined to infer that it was *h₁ because it lengthens the preceding vowel without changing its quality.

*h₃ligos [ŏligos] > Ancient Greek ὀλίγος [olígos], from which comes English oligarch.

*h₃migʰ- [ŏmigʱ] “mist” > Ancient Greek ὀμίχλη [omíkʰle:] > Modern Greek ομίχλη [omíkhli].

*h₃nh̥₃-men- [ŏ̥nómen] “name” > Ancient Greek ὄνομα [ónoma] > Modern Greek όνομα [ónoma].

*h₃nobʰ-l-on- [onóbʰlon] “navel” > Ancient Greek ὀμφαλός [ompʰalós] > Modern Greek ομφαλός [omfalós].

*h₃reǵ-to- [ŏregtʰo] “right” > Ancient Greek ὀρέγω [orégo:].

An analytical problem is presented by *h₁dont or *h₃dont [ɵ̥dont] “tooth”. The Ancient Greek reflex ὀδόντος [odóntos] is indicative of an initial *h₃ in Proto-Indo-European (which is Kroonen's analysis), but Ringe relates this word to the stem *h₁ed [ɛd], “eat”. According to the latter analysis, the initial *e (the regular descendant of *h₁ in this context) assimilated to the [o] of the following syllable, *-dont.

(f) Noninitial syllabic *h₃

*ḱh₃nid- [kɵníd] “nit” > Ancient Greek κονίδος konídos > Modern Greek κόνιδα [kónɪða].

*h₃nh̥₃-men- [ŏ̥nómen] “name” > Ancient Greek ὄνομα [ónoma] > Modern Greek όνομα [ónoma]. Further evidence for the second h̥₃ [o] comes from Latin nōmen.

*ǵʰlh₃-ros [g̟ʲʱlo̥ros] “gold/yellow” > Ancient Greek χλωρός [kʰloros] “yellowy-green” (whence English chlorine).

(3a)Offglide *eh₁ [eh], [e:], [eə]

*bʰleh₁- [bʱle:], earlier perhaps [bʱleə] “bleat” > Latvian blēt, Latin fleō “weep”.

*dʰéh₁-ti- [dʱe:ti] “deed” > Ancient Greek θέσις [tʰésis]. Additional evidence of *h₁ pronounced as [e] comes from the zero-grade form *dʰh₁-tó-s > Ancient Greek θετός [tʰetós] > Modern Greek [θetós] (see 2b above)

*ǵʰeh₁- [g̟ʱe:] “go” > Proto-Germanic *gēn ≳West Frisian gean. *ǵʰeh₁-ro- [g̟ʱe:ro] > Ancient Greek χήρα [kʰe:ra] “person left behind, widow”.

*kh₂p-éh₁- [kapé:] “have” > Proto-Germanic *habēn.

*leh₁-d- [le:d] “let”; *leh₁- > Latin lēnis.

*méh₁nos [me:nos] “moon” > Latin mēns-is “month”, Ancient Greek μήν [mě:n] “month”.

*seh₁- [se:] “to sow” > Slovenian sejáti.

For evidence for *eh₁ pronounced as a long [e:], see the derived forms *seh₁-to-

[se:to]

and *séh₁-mn̥ [se:mn̩] “seed” > Latin sēmen,

Ancient Greek ἧμᾰ [hê:ma].

*kʷieh₁- [kʷie:], *kʷieh₁-to- [kʷie:to] “while”; Latin quiēs.

*yeh₁-ro- [je:ɾɵ] “year”. Germanic (e.g. Anglo-Saxon ġēar [je:ər], Gothic jēr) provides the best evidence for the pronunciation of this *eh₁ as [e:]; the Ancient Greek cognate ὥρᾱ [ɦó:rɐ:] is from the o-grade *yóh₁r-eh₂.

The acoustic-phonetic similarity between [eh] (i.e. [ee̥]) and [e:] may

be seen in Southern British English tokens of nest, which often

show substantial devoicing in the latter 40-50% of the vowel, i.e.

[nehst]. The spectrogram below is typical.

(3b) Offlide*eh₂[a:]~[ɐ:]~[ɑ:] < [éa] < [éħ]

*bʰeh₂ǵ- [bʱɑ:g̟ʲ], earlier [bʱeɑ̆g̟ʲ] “beech” > Proto-Hellenic *pʰāgós > Doric Greek φᾱγός [pʰa:gós], Attic Greek φηγός pʰēgós, Latin fāgus; Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian bazga [bʱɑzgɑ̆]. (The [g] in this word is part of a suffix, not a reflex of PIE *ǵ. Rather, *ǵ > z in Slavic.)

*bʰeh₂ǵʰ-u- [bʱa:g̟ʲʱ—] “bough” > Proto-Hellenic *pā́kʰus > Aeolic Greek πᾶχῠς [pâkʰus]. (This word and the previous are a minimal pair in PIE, with *ǵ- in “beech” vs. *ǵʰ- in “bough”. The suffix vowels are also different in Proto-Hellenic: o vs. u.)

*bʰr(H)-eh₂- [bʱr̩hɐ:], earlier [bʱr̩heħ] “bore”; *bʰorH-eh₂- [bʱorhɐ:] > Proto-Italic *forāō > Latin forō “I bore”. (I take the laryngeal in the first syllable of *bʰr(H)-eh₂- to be *h₁, due to its later “transparency”.)

*bʰréh₂tēr [bʱrá:te:r] “brother” > Sanskrit भ्राता [bʱra:ta], Irish Gaelic bráthair, Scottish Gaelic bràthair, Czech bratr, Latvian brālis, Latin frāter.

*Heh₃l-én-eh₂- [ho̥:léna:] “ell” > Latin ulnā ≈ Proto-Albanian *ulnā, Gothic aleina “cubit”.

*péh₂‐ur [pa(ħ)ur] “fire”. Primary evidence for reconstructed *éh₂ in this word comes from its spelling in cuneiform Hittite 𒉺𒄴𒄯 pa-aḫ-ḫur /paḫḫur/ and Luwian 𒉺𒀀𒄷𒌋𒌨 pa-a-hu-u-ur /pāhūr/.

*preh₂- [pʰreɐ] “first”. Most reconstructions do not specific which laryngeal it was, e.g. Kroonen *prH-mH-on-, Ringe *pr̩H-mós; Doric Greek πρᾶτος [prâtos] (Attic Greek πρῶτος) supports the possibility that it was *h₂.

*leh₂s- [lɐ:s] “lust” > Latin lascīvus (whence English “lascivious”), Bosnian-Serbian-Montenegrin-Croatian laskati “to flatter”. Purely for the pronunciation, compare South Levantine Arabic لحس [læħas] which, with the second vowel edited out, sounds like [læħs].

*mon-eh₂- [monɐ̤ɦ] “mane”. This simulation has breathy voice, rather than voiceless pharyngeal frication, simply because of the nearest source recordings that I could find; I do not mean to claim that *h₂ was pronounced with breathy voice (though it might have been). The vowel quality in the suffix -eh₂ is inferred from other nouns (such its regular development into Proto-Germanic -ō). With different vowels in the first syllable, compare this with the pronunciation of Emirati Arabic مَنْح [mænħ] and مَنَحَ [mænɐ̤ħɐ̤].

*ml̥h₂-téh₂ [ml̩:teħ] “mould” > Ancient Greek μάλθα [maltʰa] “a soft mixture of wax and pitch”.

*peh₂- [peħ, peɐ̥] “food”. Evidence that *eh₂ was or came to be pronounced as [a] comes from Latin pāstum and Hittite 𒉺𒄴𒄩𒀸𒉡𒍣 pa-aḫ-ḫa-aš-nu-zi /paḫḫ(a)šnuzzi/. Note also Sanskrit पाति [pa:ti] “protect”, पातृ [pa:tr̩] “protector”. The word ph₂tḗr [pɑté:r] “father” is related, from *peh₂- “to feed, protect” + *-tḗr (agentive suffix), literally “one who protects/feeds” (see section 2d, above).

*priH-eh₂- [pʰri:ɐ:] “friend” > Polish przyjaciel, Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian prijatelj.

*gʰleh₂dʰ [gʱlɐ:dʱ], earlier [gʱleɐdʱ] “glad”. *gʰl̥h₂dʰ-ró- [gʱlɐdʱro] > Latin glabrō (from which came Spanish and Italian glabro, English glabrous), Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian gladak.

*ḱerdʰ-eh₂- [k̟ʲerdʱeɐ], earlier [k̟ʲerdʱeħ] “herd” > Proto-Slavic *čerda > Slovenian čreda.

*h₂roh₁(ǵ )-eh₂- [ɐ̥ɾo:gɐ́:] “reck-”. Classical Greek ἀρωγή [aro:ge:] “aid” has final [e:], whereas we expect *eh₂ > [ɐ:], but note Doric Greek ἀρωγά [ɐro:gɐ́].

*surgʰ-eh₂- [surgʱa:] “sorrow”. Evidence for [a] comes from e.g. Old High German sorga, Old Church Slavonic/archaic Bulgarian срага [srága].

*steh₂- [steɐħ] “stand”; *stí-steh₂-ti “to be standing” > Proto-Indo-Iranian *sištha- > Vedic Sanskrit तिष्ठति [tíʂʈʰati] .

*sweh₂d-u-s [swɐ:dus] “sweet” > Sanskrit स्वादु [swa:du], Balochi واد [wa:d] “salt”, Latin suavis.

*dnǵweh₂ [dn̩g̟ʲwɐħ] “tongue” > Old Latin dingua > Latin lingua.

*wĺ̥h₁-neh₂- [wl̩énaħ] “wool” > Macedonian

волна [volna],

Latvian vilna,

Proto-Italic *wlānā > Latin lāna, Sanskrit ऊर्णा [ú:rɳa:].

(3c) Offglide *eh₃

*bʰléh₃-e- [bʱlo:ə], earlier [bʱléŏə] “blossom”. *bʰléh₃-s > Latin flōs (whence English floral).

*ǵnéh₃- [g̟nəŏ] “know” > Ancient Greek γνώση [gno:se:].

*gʷeh₃-u-s [gwo:us] “cow” > Ancient Greek βοῦς [bous], Persian گاو [gov], Latin bōs (whence English bovine), Scottish Gaelic bò. The long [o:] derived from *eh₃ later exhibits a kind of “fission” into [au] in Dari گاو [gæu] and Sanskrit गौहू [gɑ́uhu].

*Heh₃l-én-eh₂- [ho̥:léna:] “ell” > Ancient Greek ὠλένη [o:léne:] > Modern Greek ωλένη [oléni] “ulna”; Armenian ոլոք olokʿ “shinbone”, Latvian olekts “ell”.

In *gʷi-gʷh₃-(u)ó‑ “quick”, evidence

for *h₃ comes largely from its unreduplicated stem *gʷiéh₃-, the

suffixed form of which *gʷiéh₃-uo‑ > Proto-Hellenic

*dʲōwós >

Ancient Greek ζωός

[dzo:ós] > Modern Greek ζώο [zoʷo] “animal”, motivating the reconstructed sequence of vocoids *éh₃-uo-

> [o:ʷo].

(3d) Onglide *h₁e

*h₁és-mi [ə́smi] “am” > Ancient Greek εἰμί [eimí], Armenian եմ [em].

*h₁és-ti [ésti]

“is” > Ancient Greek ἔστι [ésti], Latin est > French est

[e],

Romanian este [jeste]; Bosnian jeste, Lithuanian esate

[ˈɛ̆æ̀sɐte].

*h₁ér-t- [he:rt], earlier [hɘrt] “earth” > Ancient Greek ἔρα [éra:], Armenian երկիրը [jerkir(a)] “country”, Zazaki her. Cf. the Scottish pronunciation of earth, [e:ɹθ].

*h₁éd- [ɛd] “eat” > Latin edō, Ancient Greek ἔδω [édo:] > Modern Greek εδώ [eðó:], Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian jedem.

*h₁éǵh₂ [heɟɐ̥] “I” > Latin ego, Ancient Greek ἐγώ [egó:], Modern Greek εγώ [eɣó:], Armenian ես [jes].

*h₁eih₁-so- [(h)ei(h)so] “ice”. Direct evidence for an initial *h₁e is lacking, as there are few cognates outside Germanic. Digor Ossetian ех [ex] or [jex] may be pertinent, but I have no recordings of them. Evidence for the medial *ih₁ comes from reflexes with long [i:], such as Proto-Germanic *īsa > Old English īs,West Frisian iis.

*solh₁-éie- [soleiə] “sell”. Evidence for *h₁e > [e] comes from the e-grade form *selh₁- [selɘ] > Ancient Greek ἑλεῖν [helein].

In *yu(H)-e [juɦe] “you”, I take the vague reconstruction H to be probably *h₁-, as it does not alter the quality or quantity of the following *e. Cf. the Armenian reflex ձեզ [dᶻɛz].

(3e)Onglide *h₂e[ɐ] < [ħɐ] < [ħe]

*h₂eǵ-ro-s [ɐg̟ʲɾós], earlier [ħɐg̟ʲrós]

“acre” ≳ Ancient Greek αγρός [agrós], Latin ager, Sanskrit अज्र [ɐ́ʤɾɐ]

> Hindi [ɐʤíɹ̝ɤ].

*h₂el-u-t [ħɐɫʊt], earlier [ħɛlʊt] “ale” > Lithuanian alu, Latvian alu.

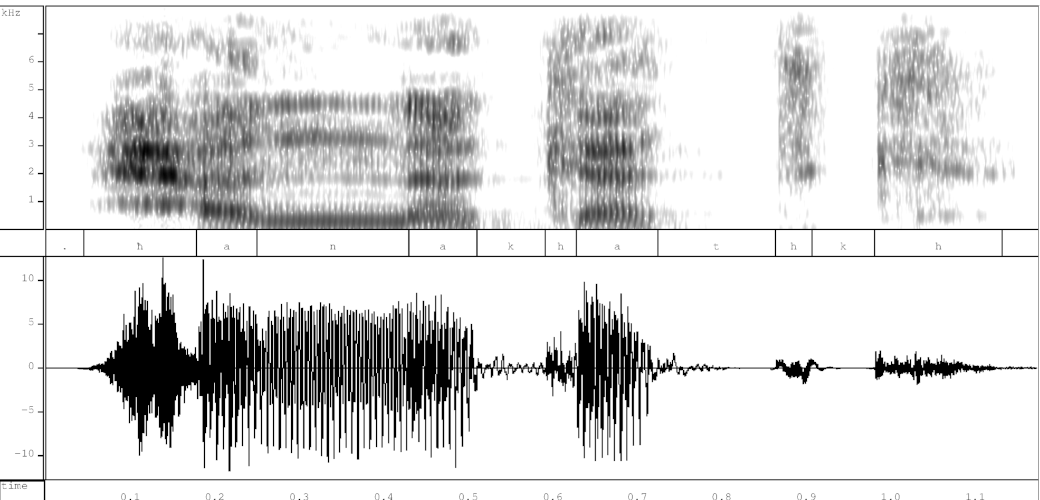

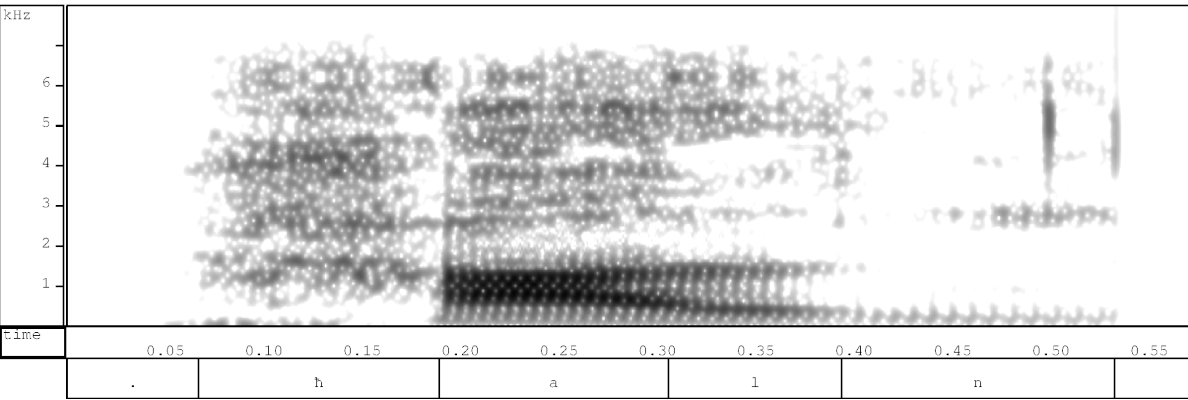

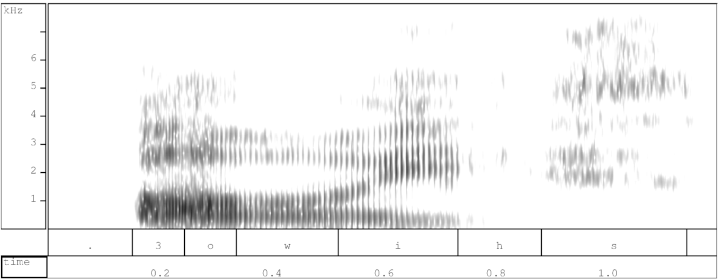

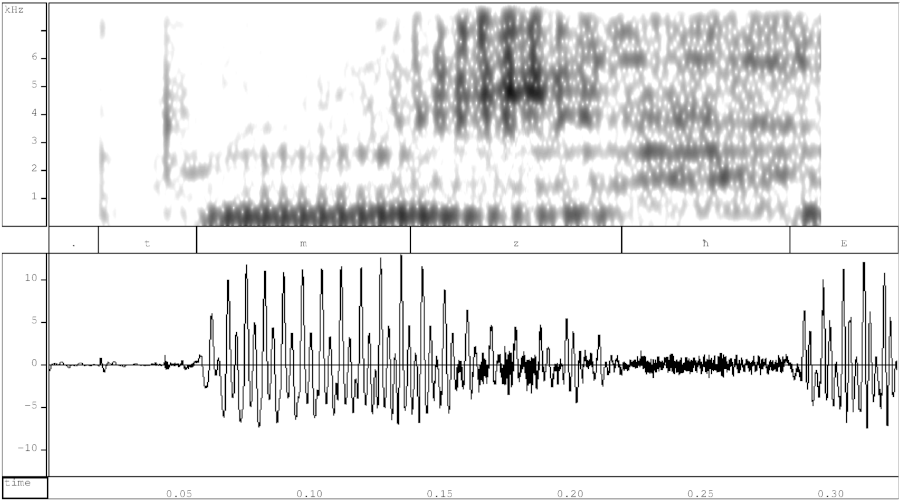

*h₂el-nó- [ħɐln—] “all” > Sanskrit अरण्य [ɐɾɐnjɐ] “wilderness”. In the spectrogram of *h₂el-nó- [ħɐln—] below, the very high first formant and relatively low second formant of [ħ] are continuous with the high F1 and low F2 of the following [a]:

Compare the pronunciation of Iranian Arabic حَالَ ḥalə [ħalə]:

and Albanian hallo (proxy for Proto-Germanic *hallo“hall”):

*h₂enk- [ħaŋk] “angle” > Ancient Greek ἄγκος [áŋgos], Iron Ossetian æнгуыр [æŋgur], Sanskrit अङ्क [áŋka], Latin ancus “bent”, Welsh crafanc “claw”.

*h₂eng- [ħæŋg] “ankle” > Ancient Greek ἀγκύλος [aŋgýlos] “curved”, Persian انگشت [ængʊʃt], Siraiki [ɐŋgutʰɑ:] “thumb”, Sanskrit अङ्गुरि aṅgúri- > modern Hindi pronunciation अंगुली [aŋguli] “finger”, Latin angulus.

*h₂en-tero- [anteɾo] “other” > Latin anterior, alter, Lithuanian antra “second”.

*h₂ebol [ħɑboɫ] “apple” > Welsh afal, South Slavic (e.g. Macedonian) jabolko, Bosnian jabuka.

*h₂erH-mos [armos], earlier [ħer:mos] “arm” > Ancient Greek ἁρμός [harmos], Modern Greek αρμός [armos] is a good example of [ħe] > [a]. Compare the pronunciation of Algerian Arabic حَرَمَ [ħaram]; with the second vowel deleted, it sounds like [ħarm].

*h₂e-h₂s- [ħaχs] “ash”, possibly a reduplicated form of *h₂es- “burn” > Old Latin asa > Latin ara. Further evidence for the initial *h₂ coming to be pronounced as [a] may be the zero-grade form *h₂sús-ye- > Proto-Hellenic *ahúhyō > ahuo > Ancient Greek αὔω hauo (no suitable recordings available).

Related to the foregoing *h₂eh₂s-

“dry”, *h₂sous- [ɑ̥sous] = [ħ̩sous] “sear, sere”. Middle

Persian 𐭧𐭠𐭪 xāk “dust, earth, grave” > Persian خاک [xɑk], خاکی [xɑki]. In these forms, the initial

*h₂ colours the *e > a and comes to be pronounced as [x] or [χ].

*h₂eus- [hɘʊs] “east”, as in Ancient Greek ἠώς [e:ó:s], has a more advanced vowel quality than in *h₂ous [hɔʊs] “ear”. Note the monophthongal outcome [u] in Sanskrit उषस् [uʂá:s] and Russian утро [útra]. *h₂eus- also developed into Proto-Italic *auzōs > Latin Aurora “Dawn” and auster, which lies behind Austria i.e. Österreich, the “eastern kingdom”.

*h₂eḱ- [ħʌk̟ʲ], from earlier [ħek̟ʲ] “edge” > Ancient Greek ἀκίς [akís], Latin ācer, Persian آس [ɑ:s] “millstone”, آهن [ɑ:han] “iron”, Balochi آسِن [ɑ:sɪn] “iron”. Compare the pronunciation of Algerian Arabic حك [ħʌk:] and Emirati Arabic حَكَّ [ħɐk:æ].

*h₂eḱ-mon- [ħek̟ʲmon], later [ħak̟ʲmon] “heaven” > Ancient Greek ἄκμων [akmo:n] “anvil, meteoric stone, meteorite”, Lithuanian akmuõ “stone”

*h₂éug- [hɑug] “eke” > Latvian augt “grow”, Lithuanian aukštas, Latin augeō, auctis, Augustus, Ancient Greek αὐξάνω [auksáno:].

*h₂él-io-s [ɐlios], earlier [ħelios] “else” > Latin alius, Ancient Greek ἄλλος [ál:os], Armenian այլ [ail].

*h₂emǵʰ-u- [ħaŋgʱu] “Eng(lish)” (a root meaning “narrow”) > Latin ango “choke, constrict”.

*h₂ep-ó [apó], earlier [ħapó] “off” > Ancient Greek ἀπό ≳ Modern Greek απο [apó], Sanskrit अप [ápa]; comparative *h₂ep-tero- [æptərə] “after”.

*h₂éi-es- [ħʌĭes] “ore” > Latin aes, Sanskrit अयस् [ajas].

*h₂en-tero- [anteɾo] “other” > Latin alter, anter-ior, Sanskrit अन्तर [antara], Lithuanian antra. For a possible earlier pronunciation, with an initial pharyngeal fricative, consider the first syllable of Emirati Arabic حَنَّت [ħæn:æt].

*(h₂e-)h₂oik- [ɐħɑik̟ʲ] “owe”. Tocharian aik- provides supportive evidence for the e-grade stem *h₂eik-, for which the initial *h₂e- would be the inferred or expected reduplicative prefix.

*ǵʰh₂ens [g̟ʲʱɐns] “gander, goose” > Urdu ہنس [hans] ≃ Proto-Italic *hāns > Latin anser.

*sh₂ei-ro- [sɐiro] “sore”, a form of *sh₂ei- [sɐi].

Evidence of *h₂ > [a] comes from Latvian saiklis, Latin saeta.

*sth₂-énti [stɐnti] “stand”. Related form *stéh₂-ti- “stead” > Ancient Greek στάσις [stásis]. See also Ancient and Modern Greek στατικός [statikós], σταθμός [staθmós], Polish stać, Welsh gwastad, Armenian ստանալ [stanal]. Inconclusive evidence for h₂ as an open vowel comes from Sanskrit तिष्ठति [tɪʂʈʰɐti] and Persian ایستادن [istɑ:dæn].

*kóuh₂-e- [kóuɐ̥], earlier [kóuħe] “hew” > Bosnian kovač “smith”.

tn̥h₂-eŭ- “thin” > Ancient Greek τᾰνᾰός [tanaós], Irish tanaí, and (historically — the vowels have subsequently changed) Welsh tenau [tʰɛnɛ:] and Scottish Gaelic tana [tʰanɛ̠].

(3f) Onglide*h₃e

*h₃esk- [osk] “ash (tree)” > Ancient Greek ὀξύα [oksýa], Modern Greek οξιά oksia.

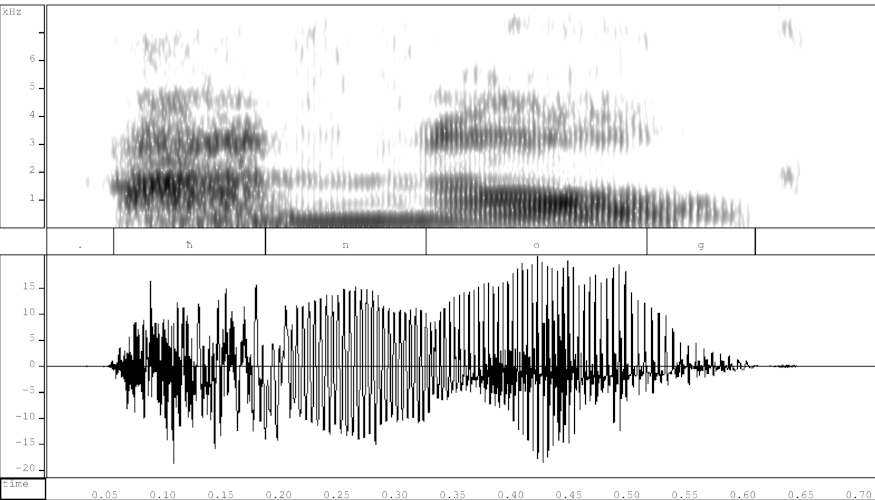

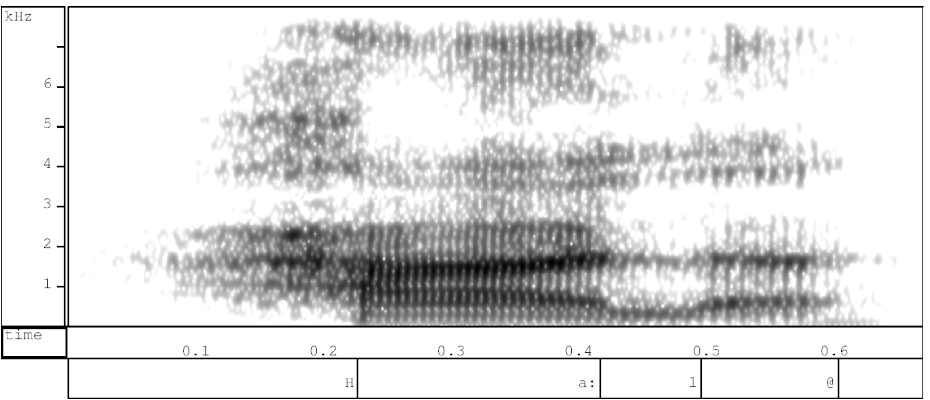

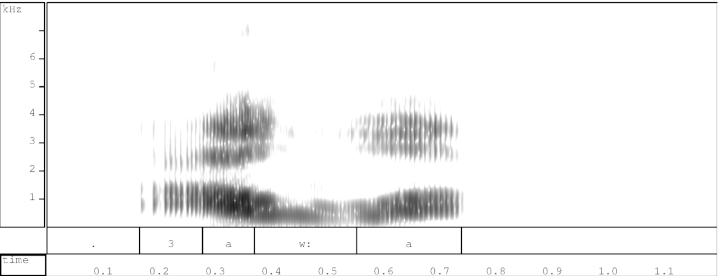

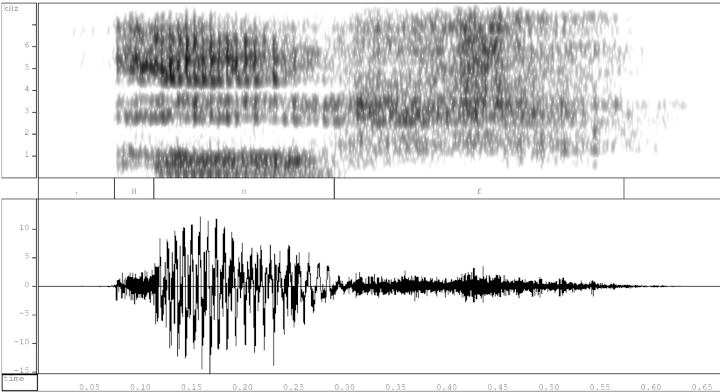

*h₃éu-i-s [ʕo:is] “ewe”. Ancient Greek ὄις [oís], Latin ovis, Slovenian ovca [owtsa], Bosnian ovca, Armenian հովիվ [hovif] “shepherd”. For an example of a similar word with an initial voiced pharyngeal approximant, compare South Levantine Arabic عوّى [ʕaw:a] “to bark”:

|

| Above: spectrogram of simulated *h₃éu-i-s [ʕo:is]; below: spectrogram of South Levantine Arabic عوّى [ʕaw:a]. |

|

Since *h₃ caused *e to become lip-rounded, it seems reasonable to think that *h₃ was itself rounded, either as a primary (contrastive) feature or as a secondary (reinforcement or enhancement) feature. These two possibilities could have played out like this, for example:

*h₃e [ħʷe] = [o̥e] > [ħʷo] = [o̥o] > [o]

or *h₃e [ʕe] = [ɑ̆e] > [ɔ̆e] (“emphatic rounding”) > [o]

Phonological contrasts between unrounded [ħ] and rounded [ħʷ] are not cross-linguistically common, whereas the second possibility (a contrast between a voiceless pharyngeal [ħ] vs. voiced pharyngeal [ʕ]) is familiar from Semitic linguistics. An association between pharyngealization and lip-rounding is attested from (i) adaptation of Arabic loan-words into other languages, (ii) dialect variation in Arabic, and (iii) the acoustic theory of speech production. We examine each of these in the following three sub-sections.

Adaptation of Arabic loan-words into other languagesJakobson (1957: 512) writes “Often labialized consonants are substituted for the corresponding pharyngealized phonemes of Arabic words by Bantus and Uzbeks, unfamiliar with such “emphatic” articulations: ṭ > tʷ, ṣ > sʷ, etc. (s. Polivanov, p. 109f[ootnote].). Instead of the back orifice, the front orifice is contracted.”

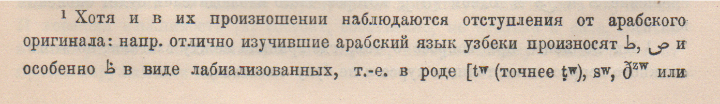

But this is not quite what Polivanov wrote. Rather, the footnote in question reads [in Russian]:

“Although in their pronunciation there are deviations from the Arabic original: for example, Uzbeks who have studied Arabic well pronounce ص ,ط and especially ظ as labialized, i.e. in the form [tʷ (more precisely ṭ̣ʷ), sʷ, ðzw, zʷ or ðʷ], and ض even in the form [w̤] (instead of [lz]; in addition, they often have a mixture of ظ and ض in one [ðʷ], which often the observer will evaluate as w).” (Polivanov, p. 109 footnote 1)

Jakobson (1957: 513) is somewhat more accurate in saying: “Furthermore, there is a tendency to emit the pharyngealized phonemes with a protrusion and slight rounding of the lips; on the other hand, the rounded phonemes occur with a slight narrowing of the pharynx to reinforce the effect of labialization.” In other words, lip rounding is an enhancement feature of pharyngealized consonants, not a replacement for pharyngealization.

Although the Polivanov reference only mentions Uzbeks, and not “Bantus”, some relevant data from a Bantu language, Swahili, is given by Tucker:

“In some words derived from Arabic words in “sad” [i.e. the letter ص ṣ [sˁ]] velarization is heard, sometimes in the form of a following w-sound. safi or swafi (clean). But note also the Mombasa pronunciation sʷisʷi for sisi (we).” (Tucker and Ashton 1942: 93, ⁋ 82)

“The ط ( t̴) of Arabic is carefully distinguished by most speakers of good Swahili from normal Swahili t, either by being velarized or else produced with a slight following -w- sound ...

Similarly the ص (s̴) of Arabic is carefully distinguished by these speakers from normal Swahili s in the same way. This will account for spellings like swafi for safi (clear), haswa for hasa (exactly)” (Tucker 1946, ⁋ 253‒4)

Rounding of “emphatic” consonants /sˁ/, /tˁ/ and /ðˁ/ is a normal feature of the local Arabic dialects, not just a peculiarity of the Swahili pronunciation of Arabic words. For example, Glover (1988:36) notes that:

The citations given above are somewhat tangential in relation to the nature of *h₃, as they refer to lip-rounding as an enhancement feature of pharyngealized obstruents, rather than as a feature of primary pharyngeal consonants such as [ʔ] or [ħ].

In Arabic and some other Afroasiatic languages, vowels in the environment of pharyngeal or pharyngealized consonants are very often pronounced with a more retracted quality, e.g. /ʕa/ > [ʕɑ] (“emphatic retraction”), e.g. Emirati Arabic نعم [næʕɐm] (unretracted) vs. Jordanian [nɑʕɑm] (retracted). Compare the two vowels in South Levantine Arabic أنعم [ʔænʕɑm], the first of which is in a non-pharyngealized syllable and is unretracted, the second of which follows a pharygneal approximant and is retracted.

Although low back vowels often become associated with rounding, as an enhancement feature (Old English man ~ mon), secure examples of ʕ > o are hard to find. In Punic, baʕal “Ba'al” > baʕl > bol, but the latter development may be part of a more general shift in the vowel a: > o, “Canaanite rounding”, rather than a specific development of ʕ; Crellin (2019) shows that in the adaptation of consonant signs to the representation of vowels in neo-Punic, `ain <ʕ> is most usually used for /a/, with /o/ most usually written using 'aleph, <ʔ>, contrary to their sound value in the Greek adaptation of those Canaanite letters.

Labialization as an enhancement feature of pharyngeals according to the acoustic theory of speech production.

Although the lips and the tongue root (which is retracted in pharyngealization) are anatomically separate articulators, the phonetic association between pharyngealization and rounding is readily understandable if we consider their similar acoustic effects, i.e. lowering of F₂ and F₃ formant frequencies. It was for this reason that Jakobson, Fant and Halle (1952) proposed the use of a single distinctive feature, [+flat], to express lip-rounding and/or pharyngealization. Although their system of phonological features is no longer widely used, the underlying insight concerning their acoustic similarity remains valid. More recently Mrayati, Carré and Guerin (1988) showed that a reduction in the area of the vocal tract at the lips reduces F2 and F3 (and F1), and so too does a reduction in the area of the vocal tract in the region of the tongue root/epiglottis. Their calculations therefore enable us to understand why lip-rounding may occur as an enhancement feature of pharyngeal constrictions. However, it is now necessary to explain why *h₂ (here modelled as [ḁ] or [ħ]) is not associated with lip-rounding. Since it is not, I infer that there was not as much tongue retraction for *h₂ (here modelled as [ḁ] or [ħ]) as for *h₃. In order to generate voiceless pharyngeal friction, it is not actually necessary to greatly retract the tongue; it is sufficient to ensure that the rate of air flow through the pharynx is high enough to give rise to audible pharyngeal friction, which is easily achieved when the glottis is held wide open. Therefore, there is an acoustic correlation between the voicelessness of *h₂ and its not causing lip-rounding. In living languages, [ħ] is well attested in the context of front, unrounded vowels; for example, in Tashlhiyt Berber bumħnd [bumħɛnd] or tmzħ [tm̩zħɛ], in which the spectral properties of the [ħ] are continued (with voicing) in the following low, front (putatively epenthetic) vowel [ɛ] (labelled “E” in the figure below). |

| Spectrogram and waveform of (above) Tashlhit Berber bumħnd and (below) tmzħ, as spoken by Mohamed Elmedlaoui. |

|

In section 2 we examined the vowels heard when the three laryngeals become vocalized, and in section 3 we examined their effects on a neighbouring vowel, specifically /e/. But what are there effects on the other Proto-Indo-European vowels, specifically /o/, /u/ and /i/?

Onglide *h₁o, *h₁u and *h₁i

In (3d) we saw that *h₁e > e, with little or no explicit evidence for the existence of *h₁ other than abstract structural considerations of system regularity etc. A similar situation obtains with *h₁o. For example:

*h₁oi-no-s [oinos], “one” > Ancient Greek οἶνος [oinos] “one (on a dice)”, Proto-Italic *oinos > Old Latin oinos > uinus > Latin ūnus. The proposed *h₁ is not strongly evidenced, and some philologists do not reconstruct it in this word (e.g. Ringe 2006 p. 53: *óynos).

*polh₁-uo [polwo] “fallow”. The fact that Sanskrit पलित [palɪta] “grey” has a front vowel between [l] and [t] is evidence of a syllabic (vocalic) realization of inter-consonantal *h₁ in *polh₁-tos [polɪtos].

*melh₁-uo- [meləwɔ] “meal” (ground food); we here follow Kroonen's reconstruction for the avoidance of argument, though others postulate a slightly different stem *melh₂- > Proto-Hellenic *mólā > Doric μύλαν, Attic and Homeric Greek μύλη múlē “mill”, Latin molāris, from which comes English molar.

*ph₁-i-ont- [piont] “fiend”. Evidence for *h₁ comes from the related full grade inflection in *péh₁-mn̥ > Proto-Hellenic *pēmə > Ancient Greek πῆμα pêma “misery” (no recording available).

*kouh₁-is [ko:his] “show” > Marathi कवि [kəvi] “poet”. Evidence for *h₁ pronounced as [ɘ] (later [e]) in this stem may come from Ancient Greek κοέω [koéo:], Latin cave. For the lengthening effect of *h₁ on a preceding *u, see *(s)keuh₁- [skouˑ], below.

*h₁uksen [ɦuksɘn] “ox” > Sanskrit उक्षन् [ukʃɐn]. Since the initial laryngeal does not affect the vowel [u], some (e.g. Ringe) don't reconstruct an initial laryngeal in this word, and perhaps by Occam's razor we should not. The fact that the initial laryngeal fricative in this simulation is breathy-voiced is accidental, and I do not mean to claim that this was its pronunciation in Proto-Indo-European (though it may have been, as Pyysalo 2013 argues).

*h₁upo [hupo] “up”, from earlier

*supo.

This derivation makes much sense if *h₁ was [h], because s > h is a

cross-linguistically common sound change.

*somh₁-o- [somo] “same, some” is reconstructed by some with an indefinite laryngeal, H, because it is not strictly possible to determine whether it should be *h₁ or *h₃ as the following vowel is *o. The presence of a laryngeal is motivated to an extent by the zero-grade form *smh₁-o- [sm̩:o] “some”, with a syllabic nasal that is may be presumed long.

Offglide *oh₁ [o:], *ih₁ [i:], *uh₁ [u:]

As with *eh₁, *h₁ lengthens a preceding /o/ without altering its quality. The phonetic outcome is therefore similar to or the same as *eh₃, meaning that for words attested with long [o:] in daughter languages, care must be taken to determine whether it comes from *eh₃ or *oh₁. In reconstructed laryngeals of uncertain quality, often transcribed by others as H, I am inclined to propose that its value is *h₁ because it lengthens the preceding vowel or sonorant consonant without changing its quality.*dʰoh₁- [dʱo:] “do”. *dʰóh₁mos > Ancient Greek θωμός [tʰo:mos] “heap”, Proto-Germanic *dōmaz > Old Norse dómr “doom”.

*dwóh₁- [dwoh] “two” (Ringe p. 98). Kroonon proposes *duo-, without laryngeal. The simulation here happens to exhibit devoicing at the end of the vowel, in order to illustrate what a pronunciation of h₁ as [h] sounds like, by way of exploring possible phonetic reconstructions.

*h₂roh₁(ǵ )-eh₂-

[ɐ̥ɾo:gɐ:]

“reck-” ≳ Ancient Greek ἀρωγή [aro:ge:] “aid”.

Likewise, *h₁ lengthens a preceding /i/ or /u/ without altering its

quality (but cf. section 4 below):

*wih₁ro- [ʋi:ɾo] “were(wolf)” > Lithuanian výras, Latvian vīrietis, Avestan vīra-, Sanskrit वीर [vi:rá], Hindi वीर [vi:r].

*kʷih₁-l-eh₂-, from *kʷih₁- [kʷi:],

zero grade of *kʷieh₁ [kʷie:] “while”; cf. *kʷiéh₁-ti-s

> Latin quiēs.

*tri-tih₁o- [triti:o], from earlier [triti:ho] “third” > Sanskrit तृतीय [tr̩ti:a].

*muh₁s- [mu:s] “mouse” > Latin mūs, Sanskrit मूष् [mu:ʂ], Persian موش [mu:ʃ].

*syuh₁- [sĭu:] “sew” > Lithuanian siūti.

*(s)keuh₁- [skouˑ] “show” > Ancient Greek κῦδος [kʉ:dos].

᷈*suh₁- [su:h] “sow” (female pig) > Latin sūs, Ancient Greek ὗς [hʉ᷈:s]; *suh₁-kas > Balochi ہوک [hu:k], Persian خوک [χu:c]. For medial *h₁ as [h], see *suh₁-īno- [su:hi:no] “swine”.

*h₃bʰruh₁-s [ŏ̥bʱɾʉ:s] “brow” > Ancient Greek ὀφρῦς [ophrŷ:s].

*suh₁-nus [su:nus] “son” ≳ Lithuanian sūnus.

*h₂o-

*h₂oḱtṓu “eight” > Tajik ҳашт [haʃt].

*h₂ous [aus], from earlier [hɐus], [hɒus-es] “ear” (with a backer vowel quality than in *h₂eus- [hæus] “east” ) > Ancient Greek οὖς [ǒ̝ùs] ≈ Lithuanian ausìs, Persian هوش [hu:ʃ].

In *h₂e-h₂oik- [ɐħɐik̟ʲ] “owe”, evidence for *h₂oi may perhaps be drawn from Proto-Germanic *aigan, but that is not decisive because Proto-Indo-European *oi developed regularly into Proto-Germanic *ai, so the laryngeal is here not strictly necessary to reconstruct here. The *e and following *h₂ are in separate syllables, so the h₂ does not lengthen its preceding vowel. With the second *h₂ syllabified as a syllable onset to the following *o, I have simulated it with a voiceless fricative that colours the following vowel to [ɐ]. Variants with backer vowels such as [ɔi]~[ɒi] are also conceivable, but not necessary (see discussion in 3f, above).

*h₂u-

*h₂up/kʷ-no- [ħup-no, ħukʷ-] “oven” > Sanskrit उखा [ukʰá:].

*tn̥h₂-u- [tn̩̩:u] “thin”, *tn̥h₂-u-kos (Bulgarian proxy [tn̩̩ək]) > Balochi تنک [tanak], Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian tanak. Evidence of *h₂ in this stem comes from tn̥h₂-eŭ- “thin” > Ancient Greek τᾰνᾰός tanaós (see section 3e above for further examples with audio).

*-oh₂

*-uh₂

*dʰeuh₂-, *dhouh₂- [dʱoʊɐ] “dew” < *dhuh₂- “smoke”. Evidence for *h₂- > *a comes from Hittite 𒈭𒄩𒀀𒄑𒍣 túḫ-ḫa-a-iz-zi (possibly [tɔħːáːi̯tsi]) < Proto-Anatolian *duHoyéti < *dʰuh₂-oyé-ti (?) “produce smoke”, but there are no recordings of course.

*tuh₂ [tuɐ] from earlier [tuɐ̥], [tuħ] “thou” > Tajik ту [tu:], Old English þū. *tuh₂ is Ringe's reconstruction; others propose *tuH. The main motivation for proposing a laryngeal here is to lengthen the preceding vowel length, as in e.g. Tajik, so it might equally well have been *h₁. I give a simulation of [tuɐ̥] to exemplify what it might sound like if the *tuh₂ analysis were correct, even though this currently seems unknowable. If *tuh₁ were correct, the Tajik example would be a more appropriate proxy. However, the Pashto singular oblique reflex of *tuh₂, تا taħ “thee” may present evidence of retention of the final laryngeal, and its quality is [ħ] rather than [h].

*uh₂ǵ-e- [wagə] “wake” > Sanskrit वाज [wa:ʤa]. In this simulation, it is unclear why a fricative laryngeal would vocalize, given that e.g. [ħ] is less sonorous than [u]. *uh₂ǵ-e- is Kroonen's reconstruction, though others (e.g. Ringe) propose *woǵ- ~ *weǵ-, as also does Kroonen for the Proto-Germanic causative *wakjan. But Kroonen deliberately does not distinguish between syllabic and non-syllabic variants of vocoids, so this is really just a matter of notational variation.

*h₁widʰh₁-uh₂- [hwidʰəwaħ] “widow” >

Ukrainian удова [udovɐ], Hindi विधवा [vɪdʱvɐ].

*h₃o-

*h₃okʷ [okʷ], a form of *h₃ekʷ [ʕekʷ] “eye” > Ancient Greek ὀφθαλμός [opʰ-tʰalmos] > Modern Greek οφθαλμός [ofθalmós], Latin oc-ulus, Ukrainian око [okʷŏ]. (As *h₃ is expected to cause a following *e to become rounded, this word might instead be reconstructed as *h₃ekʷ.)

This token of English off gives an example of how *h₃o

could have sounded with a devoiced vowel onset, i.e. if it were [ho—]. In

the spectrogram below it can be seen that the devoiced portion at the

beginning of the vowel has exactly the same quality as the voiced portion

that follows it, but with no voice bar at the bottom of the spectrogram,

and voiceless frication in the waveform for that portion. However, it

seems more likely to me (and various other people) that *h₃ was voiced,

not voiceless, in which case this example is not illustrative. But cf.

*h₃owis, which has voiceless reflexes.

*ih₃ [i:]

*gʷih₃-uo [gwi:wo] “quick” (zero ablaut form of *gʷiéh₃-uo-; see section 3c above) > Ancient Greek βίος [bi:os], Latin vīvō. In this context, *ih₃ > [i:].

In many cases, laryngeals appear in syllable positions in between sonorant and obstruent consonants; the sonority sequencing theory holds that they were therefore less sonorous than sonorant consonants (e.g. liquids and nasals), but more sonorous than stops, which suggests they could have been fricatives. Since laryngeals are hypothesized elements, however, there is a degree of circularity in this argument because the places in which they are proposed are hypothesized in part by awareness of this theory of syllable structure.

For example, consider the reconstruction *h₁dont [ɵ̥dont] “tooth”. The Ancient Greek reflex ὀδόντος odónt-os is possibly indicative of *h₃ (which is Kroonen's analysis), but Ringe relates this word to the stem *h₁ed [ɛd], “eat”, thus, with zero ablaut, *h₁dont [ɵ̥dont]. That *h₁ in this context became a syllabic vocoid before /d/ could be evidence that laryngeals were more sonorous than stops.

On the other hand, laryngeals were sometimes less sonorous than syllabic sonorants, as in various examples presented below (e.g. *plh₁-nó- [pl̩n-] “full”, *sl̥h₁- [sl̩:] “sell”, *wĺ̥h₁-neh₂- [wl̩:na:] “wool”), perhaps suggesting that laryngeals were intermediate in sonority between sonorant consonants and stops, giving rise to the theory that they were originally fricatives. However, such an argument is unclear because in many other contexts laryngeals were more sonorous than adjacent non-syllabic sonorants, as in the very many examples of syllabic laryngeals presented above. Such examples are more consistent with the argument of Reynolds et al. (2000) that laryngeals were primarily vocalic.

Onglide *h₁u

*h₁uebʰ- > Ancient Greek ὑφή [hʉpʰe:] “web”. In this word, *h₁ seems to be retained as an initial [h] and did not develop into a vowel such as [ɘ] in this environment; that is,*h₁uebʰ- did not develop into eweph, unlike *h₁wedʰ- [ə̥wedʰ] “wed” > *ewedna > Homeric Greek ἔεδνα éedna. Contrast this case with *h₂ués- > Proto-Hellenic *áwesa, below, in which *h₂u comes out as [ɐw].

In *h₁ŭidʰh₁-uh₂- [hwidʱəwaħ] “widow” I have not simulated an initial vowel, but rather just [h], as if this is not preconsonantal *h₁w > [ew] (for which there is no evidence) but rather prevocalic *h₁u > [hw].The second h₁- of *h₁ŭidʰh₁-uh₂- [hwidʰəwaħ] is here simulated as [ə], to illustrate the variable syllabification of *h₁.

Postvocalic *uh₁

In *h₂yuh₁n-ḱós “young”, if the *h₁ were in the same syllable as the preceding *u, we would expect it to just lengthen it, giving [ɐju:ŋkos]. However, Latin iuvencus [juˈvɛŋkʊs], Welsh ieuenctid [jəjɛŋktɪd] and Sanskrit युवन् [juvan] suggest that the *h₁ could be parsed into a separate syllable: *h₂.yu.h₁n̥.ḱós. This third syllable might feasibly have been pronounced [hn̩], but with vocalization of *h₁ as [e], a pronunciation [ɐjueŋkos] would be arrived at.

Syllabic *h₂ before u/w

is exemplified by *h₂wés- [ɐ̥wes] > Proto-Hellenic *áwesa > Ancient Greek ἄεσα [áesa] “I slept”.

Offglide *l̥h₁ [l̩:]

*plh₁-nó- [pl̩:n-] “full”; the existence of the laryngeal is motivated by e.g. the e-grade form *pleh₁-nó- > Latin plēnus, Ancient Greek πληθύς [ple:tʰýs].

*sl̥h₁- [sl̩:] “sell”. For this zero-grade form, see Bosnian slati “to send”. The existence and quality of the laryngeal are shown in e.g. Ancient Greek ἑλεῖν [helein] < *selh₁- [sele], in which *h₁- serves as a syllable nucleus (see section 3d).

*wĺ̥h₁-neh₂- [wl̩:na:] “wool” > Proto-Hellenic *wlḗnos > Ancient Greek λῆνος [le:nos]

*-lh₂

Possible evidence that *h₂ was less sonorous than *l comes from the sonority sequencing (with [l] as the syllable peak) in *ml̥h₂-téh₂ [ml̩:teħ] “mould” < *melh₂- [melħ] (a recording of Maltese melħ; compare also compare Hebrew מלח [mɪlɑχ]). The syllabicity of the *l is heard in the Sanskrit reflex मृदा mr̩da. It is then somewhat puzzling that *séh₂-l “salt” is monosyllabic ([sɐ:l], earlier [seɐl]) rather than disyllabic [se.ħl̩], but possibly [se.ħl̩] > [se.ɐl] > [sɐ:l] leads to the same end.

*-rh₁

*derh₁‑

“to tear”. The existence of a laryngeal in this word seems far from

certain, and Kroonen hedges his bets with “*der(H)”. My audio simulation

has a devoiced ending, so we can hear what [derh] would

sound like with a final [h] if that is the correct reconstruction.

*-rh₂

Evidence that *h₂ was less sonorous than *r comes from *térh₂-h₃kʷ-e (Kroonen) or perhaps *terh₂-kʷe [terɐ̥kwe] “thorough, through”. If laryngeals were fricatives, therefore less sonorous than *r, as in *tér.h₂h₃.kʷ-e [terħŏkwe] > Proto-Germanic *þer[ŏ]hwe > “thorough”, it's not clear why initial *h₁ before an /r/ in *h₁roudʰ- [hroʊdʱ] “red” or *h₁rebʰ- [hreɛbʱ] “rib” should have become syllabic vocoids. Consonantal *h₂ would be parsed as a syllable onset, requiring that the following *h₃ is syllabified as a syllable nucleus, and therefore realized as a vowel, as manifest in the second syllable of “thorough”.

On the other hand, evidence that *h₂ was more sonorous than *r

; *tr̥h₂-n̥ts > Proto-Italic *trānts > Latin trāns.

If *h₂ were more sonorous than the preceding *r, *térh₂-h₃kʷ-e would be

pronounced [teraŏkwe]. This tension in

evidence suggests that *h₂ was not inherently more or less

sonorous than *r, but rather could be realized as a consonant or a vowel

(e.g. syllable onset or nucleus), just like i/j or u/w, according to the

context in which it occurred. Both consonantal and vocalic outcomes of *h₂

are found in different languages, e.g. *h₂eydʰ- “to burn” > Albanian hithër vs.

Ancient Greek αἰθήρ [aitʰé:r].

In the zero grade of *steh₂- [steɐħ] “to stand”, i.e. *sth₂- [stɐ̥], as in *sth₂-énti [stɐnti], the cluster *th₂ is inherited as a voiceless aspirated consonant in Sanskrit, which is also preserved in Hindi. E.g. *stéh₂-ti- “stead” > *sth₂-tí- > Sanskrit and Hindi स्थिति [stʰiti] “situation, position”. This may indicate that there was aspiration in the cluster *sth₂ in Proto-Indo-European, i.e. [stʰ].

*sth₂-énti [stʰɐnti] “stand” > Sanskrit तिष्ठति ti-ṣṭhati [tɪʂʈʰɐti].

*sth₂-wéh₂-néh₂ > *sth₂-uh₂-néh₂ > Sanskrit स्थूणा [stʰu:ɳa:] “pillar”, Persian ستون [sutʰu:n] “column”.

*pelth₂- [peltʰɐ] ~ [peltħ] “field”; *plth₂- [pl̩tʰɐ] “flat”. *pl̩th₂ú- > Proto-Indo-Iranian *pr̩thú- ‘broad’ ≳ Vedic Sanskrit पृथु [pr̩tʰú-]. (Kümmel 2022 gives a similar analysis with [χ] rather than [ħ]: “*pl̩tχú- > *pr̩thú- ‘broad’ > Ved[ic] pr̥thú- = Av[estan] pərəθu-”.)

*péh₂‐ur [paħur] “fire” > Balochi پُر [pʰor] “ashes, flames”.

Kümmel (2022) says that “Laryngeal aspiration caused by *h₁ is controversial, but there are some potential examples: *pónt-e/oh- ~ *pn̩t-h- > *pántā- ~ *path- > Av[estan] paṇtā- ~ paθ-”. Audio examples: Proto-Indo-European *pont-eh₁-s [pʰontʰe:s] > Vedic Sanskrit पन्थासो [pantʰa:so], Iranian *[paθa]. I note that the aspirated [tʰ] is in this analysis /...t-eh₁.../ not actually adjacent to the *h₁, so this example might be taken as evidence of a “prosodic” aspiration feature.) The vowel length in the second syllable of Avestan paṇtā- and of Vedic Sanskrit पन्थासो [pantʰa:so] provides evidence of some postvocalic laryngeal, but because the contrasts between laryngeals were lost in Indo-Iranian, it is difficult to tell whether it was *h₁ or *h₂-.

Examples cited by Kümmel (2022): As well as illustrating *h₂ > a (e.g. in Ancient Greek μέγας [megas]), PIE *meǵh₂- “much” also exemplifies “laryngeal aspiration” with concomitant devoicing of the preceding *ǵ: *meǵh₂- [meg̟ɐ] > Proto-Indo-Aryan *maźʰā́ > Sanskrit महा mahā́ e.g. महयति [mahajati] > Hindi महा mahā. Proto-Indo-Iranian *maj́h- > Iranian *majh- > *mach- > *mac- > mas-, maθ- ‘great’, whereas in the full grade form in which a vowel intervenes between the voiced stop and following laryngeal, there is no such devoicing: *majah- > mazā- e.g. Balochi [mɐzɐn].

In some other examples of so-called “laryngeal devoicing”, an alternative analysis is possible. For example, in *nābʰ- > *nāpʰ- > Persian ناف [na:f] ‘navel’ (vs. *nabah- > nabā-), the devoiced consonant is derived from *bʰ, i.e. the root is here reconstructed by Kroonen as *h₃nobʰ-, not *b+laryngeal, as proposed by Kümmel. Similarly *wabʰ- > *wapʰ- (as in Balochi گْوَپت [gwəp]) > *waf- (as in Persian بافتن [bɑ:ftæn]) ‘to weave’ also exemplifies devoicing, but descends from *h₁webʰ-, not *b+laryngeal, according to Kroonen. Such examples might suggest that aspiration caused by laryngeals and the aspiration of aspirated plosives such as *bʰ may have been of the same phonetic character. However, if *bʰ had breathy voiced aspiration [bʱ] not voiceless aspiration, as discussed here, it is phonetically mysterious why *bʰ would have developed into *pʰ in this environment, so Kümmel's analysis seems more reasonable to me than Kroonen's.

*h₁uper- [hʉpeɾ] “over” ≳ Ancient Greek ὑπέρ [hʉpér]. *h₁uper- was the comparative of *h₁upo [hupo] “up” ≳ Ancient Greek ὑπό [hʉpó]. Related to this observation is the hypothesis that *h₁upo [hupo] derives from earlier *(s)upo. Evidence for the alternative *s- form comes from cognates in Tocharian B spe, Latin subtus. Since [s] > [h] changes are widely attested cross-linguistically, whereas changes from [s] to say [ħ], [χ] or [ʕ], or from [h] to [s] are extremely uncommon, this supports the hypotheses that *(s)upo predates *h₁upo and that *h₁upo was pronounced [hupo]. Alternatively, it is conceivable that the [h] in the Greek forms does not derive from *h₁, but comes directly from *s (but that will not work for the next example below). I simply follow the expert opinion of philologists such as Kroonen, Mallory and Adams in accepting an initial laryngeal in *h₁upo.

*h₁webʰ- > Ancient Greek ὑφή [hypʰe:] “web”. *h₁ did not develop into an [e] in this word i.e. *h₁webʰ- did not develop into eweph. Instead, there was in Ancient Greek or earlier a vowel [u] preceded by an onset [h]. Contrast this with *h₁wedʰ- [ə̥wedʰ] > Proto-Hellenic *ewedna > Homeric Greek ἔεδνα éedna, in which the initial *h₁ did develop into an [e].

*ḱieh₁- [k̟ʲe:], earlier [k̟ʲeh], “hue” developed into Persian سیاه [sijah] “black”, which provides evidence for a final laryngeal. In my small collection of recordings from Iranian languages, the final fricative is sometimes pronounced as [h], [ħ], or [x], consistent with reflexes of either *h₁ or *h₂.

*h₁éǵh₂óm “I am” > Proto-Indo-Iranian aȷ́ʰám > Proto-Indo-Aryan *aźʰám > Sanskrit अहम् [ahám] provides evidence of a voiceless laryngeal fricative remaining as the final vestige of the original *h₂.

*h₂erH-mos [ħer:mos] “arm” > Ancient Greek ἁρμός [harmos], which shows not only the a-colouring of *h₂, but also retention of its voiceless frication, albeit [h] not [ħ].

My simulation of *h₁roudʰ- [hroʊdʱ] “red” is based upon recordings of Lithuanian raudonas, which typically shows an initial [hr] or [r̥], as does the Latvian cognate ruds. It is perhaps unlikely that this pre-aspiration is in fact inherited from Proto-Indo-European *h₁, but from a phonetic perspective these examples serve to illustrate possible pronunciations rather well. It is notable that initial /r/ in Ancient Greek is spelled with “rough breathing”, likely indicating a whispered pronunciation [r̥], as in ῥῶ rhô [r̥o:].

![Spectrogram and waveform of Lithuanian raudoas, showing preaspirated initial [hr]](eastern-origins/hraudonas720p.png)

Spectrogram and waveform of Lithuanian raudonas, showing preaspirated initial [hr].

Consonantal reflexes of initial *h₂ in Iranian, Armenian, and Albanian

Kümmel (2022) notes that “h-/x- appears to be sporadically preserved in marginal Western Iranian ... Especially the cases with x- can hardly be assumed to show a “prothetic” consonant.” (Not all of the following examples are simulated in this project, as they don't have English cognates, but I have collected such examples as I could in the hope they may be useful.)*h₂ōu-ió- [χɐuio] “egg” exemplifies the retention of *h₂ as voiceless “guttural” fricatives, through Proto-Indo-Iranian *Hāwyám > Middle Persian xāyag > Persian خایه [xɑje], Balochi ہیک [hajk], Northern (Kurmanji) Kurdish [he:k], Pashto هګئ [haˈgəj], ها hau, هويه huwiya, Tajik хоя xoya. Further evidence of *h₂ coming to be pronounced as a low vowel such as [a] or [ɐ] is seen in the related form *h₂éu-is [ħɐʊɪs] “bird” > Latin avis; an initial [h] is preserved in Old Armenian հաւ haw, Modern Armenian հավ [hav].

*h₂ŕ̥tḱos “bear” > Proto-Iranian *Hŕ̥ćšas > Proto-Iranian *Hŕ̥šah > MPers. xirs > Kurdish ھرچ hirç [həɾʧ], Zazaki heş [hɛʃ], Iranian Persian خرس [xeɾs], Tajik хирс [xirs].

*h₂erh₃- “ploughshare“ ?> Manichaean Middle Persian hēš > Persian خیش [xi:ʃ].

*h₂eydʰ- “to burn” > Middle Persian hēsm/hēmag ‘firewood’ > Persian هیزم hêzom [hi:zom]; Albanian hithër.

*h₂omós “raw, uncooked” > Persian خام [χɑ:m], Balochi هامَگ hāmag; Northern (Kurmanji) Kurdish xav, Armenian հում hum.

*h₂e-h₂s- [ħaχs] “ash”, possibly a reduplicated form of *h₂es- “burn” > Middle Persian 𐭧𐭠𐭪 xāk “dust, earth, grave” ≳ Persian خاک [χɑc], [xɑk] خاکی [xɑki] “khaki, earthy” (borrowed into Urdu خاکی [xɑki], borrowed into English khaki), خاکستری [xɑkestaɾí] “grey”. In these forms, the initial *h₂ colours the /e/ to [a] and itself comes to be pronounced as [x] or [χ], and the medial *h₂ > [x] > [k]. A similar development is seen in the possible related form *h₂s-ous- [ɑ̥sous], [ħsous] “sear, sere” > Persian خشک [χoʃk] “dry”, Balochi [hʉʃk], Northern (Kurmanji) Kurdish hişk [ħəʃk].

*h₂énh₁mos “breath” > Armenian հողմ hoɫm [hɔʁm] “wind” (but this etymology is problematic, according to Kölligan), Zazaki helm [ħɐɫm] “breath, whiff”. Cf. Ancient Greek ἄνεμος ánemos, Proto-Italic *anamos > Latin animus.

*h₂noḱ- [ħɐ̥nok] “enough”, zero grade *h₂n̥ḱ [ħnk̟ʲ] > *(h)ans- > Armenian հասնել [hasnel]. In this derivation, the [a] is descended from *h₂, but whether the initial [h] is also derived from *h₂ is uncertain. Also, *h₂e-h₂noḱ- [ħɐ̥ħnok] “enough” > Albanian kënaq [kənáʧ].

*gʷerh₂-nu- [gwerɐn] “quern” > Pashto ګور [gurħ] “grave, tomb”

Possibly, *h₂oḱtṓu “eight” > Persian هشت [haʃt], Tajik ҳашт [haʃt]. The identity of the initial laryngeal is uncertain, and debated. Most other cases of a laryngeal surviving as [h] in Indo-Iranian are of *h₂; it cannot be inferred from the vowel quality [o] in e.g. Ancient Greek ὀκτώ okto and Latin octo that there was an intial *h₃, because the vowel is /o/, and if *h₃ were voiced it would be unlikely in this case. *h₁o- would also be possible. Whichever laryngeal it was, however, the initial voiceless fricatives preserved in Iranian languages support the proposal that this word began with some kind of laryngeal.

*h₃éu-i-s [howis] “ewe” > Armenian հովիվ hovif “shepherd”.

A caution: in *séh₂wl̩ [sɐʊɫ] ~ *sóh₂wl̩ [sɒʊɫ] “sun”, the Persian reflex خور [xʷor] “sunrise” (as in the place-name خراسان Khorasan, Balochi hurāsān) looks as if it may conceal a preserved form [xʷ] of the laryngeal *h₂, but this is not so: the derivation is *sóh₂wl̩ > Proto-Indo-Iranian *súHar > *húHar > *huar, so the initial fricatives in these Persian and Balochi words are actually reflexes of Proto-Indo-European *s.

In cuneiform Hittite and Luwian, *h₂ and sometimes *h₃ are written with letters that were originally (in Akkadian etc.) used for syllables containing a voiceless fricative ḫ, believed to have been pronounced with a velar or possibly uvular fricative [x] or [χ] (Huehnergard and Woods 2004 CHECK; Kloekhorst 2007:27, Huehnergard 2011). For example, in Cuneiform Hittite 𒄩𒀸𒊭𒀸 ḫa-aš-ša-aš /ḫāššaš/, “descendant” < Proto-Indo-European *h₂ems-, the first sign 𒄩 may be read with the Akkadian value ḫa, the pronunciation of which is evidenced by cognates in other Semitic languages, e.g.:

A few more Hittite examples:

In Lycian, (descendants of) *h₂ are written with consonant letters 𐊋, 𐊌 and 𐊜, philologically transcribed as k, q (=[kʷ]?) and χ, e.g. Lycian χawa- < *h₃ewis (sheep, ewe); χñt- < *h₂ent- (compare Hittite ḫant- 'in front'), e.g. χñtawati “king, the one who is in front”. The sound values of those Lycian letters are not known for certain, but their reading as velar consonants is supported by spelling correspondences with certain names in Greek, such as the place names xadawãti = Greek Καδύανδα (Kadyanda), xbane = Greek Κυανέαι (Kyaneai), and the personal names mexistten(e) = Greek Μεγασθένης (Megasthenes) and xaxakba = Greek Κακασβος (Kakasbos, a deity).

Indo-European cognates in Semitic?

Various othe connections between Proto-Indo-European and Semitic languages (i.e. other than via cuneiform script) have been proposed, whether as putative cognates or as loan words, and some of those may also be indicative of possible pronunciations of laryngeals. For example, in *h₃éu-i-s [howis] “ewe”, evidence that *h₃ may have originally been a fricative or stop could be provided by possibly related Semitic words e.g. Akkadian 𒆏𒋢 kabsu, Emirati Arabic كبش [kɛbʃ], Algerian Arabic [kɛbɪʃ], Hebrew כֶּבֶשׂ [kɛvɛʃ], if that is not an accidental similarity, as well as the cuneiform spelling used in Hittite 𒇻𒅖 (ḫāwis) and Luwian 𒄩𒀀𒌑𒄿𒅖 ḫa-a-ú-i-iš- /ḫāwīs/. Similarly *h₁er-t [hɘrt] “earth” may be cognate with Proto-Semitic *ʔarṣ́-, e.g. Hebrew אֶרֶץ [ʔeʀ̆ets], Arabic أَرْض [ʔardˁ]. Such a connection, if true, might link the pronunciation [ʔ] to *h₁.

From the colouring effects of *h₂ and *h₃ on preceding or following vowels (i.e. assimilation of those vowels to the *h₂ and *h₃), those two laryngeals must have had inherent vocalic resonances: open, non-front (though not necessarily actually back) and unrounded for *h₂ vs. open, back, and rounded for *h₃, that is, vocalic qualities around [ɐ] and [ɔ], respectively. But in combination with ablaut vowels /e and /o/ they were non-syllabic glides, i.e. [ɐ̆] and [ɔ̆]. In many languages the laryngeals affected vowels, and in Ancient Greek actually appear as vowels; but the phonetic evidence from Iranian, Armenian, Albanian and sometimes Greek, plus the orthographic evidence especially from Hittite, that *h₂ and sometimes *h₃ developed into [x], [χ] or [h], or aspiration [ʰ] that could cause devoicing of preceding consonants, suggests that *h₂ was probably voiceless. As laryngeals developed in some languages (e.g. Ancient Greek) into vowels and in other languages (e.g. Indo-Iranian) into obstruents, it is an economical explanation to suggest that laryngeals were glides with a combination of vocalic and consonantal properties, i.e. vocalic resonances (vowel-like qualities), non-syllabicity (usually) i.e. medium sonority, and for *h₂ almost certainly and for *h₁ quite probably, voicelessness.

Since both vocalic and consonantal descendents of *h₁ and *h₂ have survived to the present day, it is logically possible to argue either that the consonantal character is older or in some sense more basic, with the vocalic reflexes descending from them by "vocalization"; or that the vocalic character is older or in some sense more basic (as Reynolds et al. 2000 argued), with consonantal reflexes arising by e.g. devoicing. Either of those scenarios still looks reasonable. Nevertheless, the consensus among philologists is that the consonantal character of laryngeals is older, with the vocalic reflexes arising later. Following that scenario, I arrive at these proposals as the phonetically most likely(?) possibilities:

*h₁ was at an early stage [h] — more specifically [ɘ̥̆], though it readily assimilated to neighboring vowel qualities, causing lengthening of a preceding vowels. This *h₁ [ɘ̥] survived into Ancient Greek in its vocalic aspect as [e] (e.g. ἐννέα [en:éa]), and in Persian in its consonantal aspect as [h], [x], or [χ] (e.g. سیاه [sijah]). The derivation of *h₁upo “up”, from an earlier *supo, makes sense if *h₁ was [h], because s > h is a cross-linguistically common sound change.

*h₂ was at an early stage [ħ] — more specifically [ɐ̥̆]. Because it was voiceless, it does not require a strongly retracted tongue root to articulate a voiceless pharyngeal fricative [ħ], so it can be articulated with a non-back tongue position. In its voiceless, consonantal aspect it also survived as [h], [ħ], [x], or [χ] in Indo-Iranian, Armenian, and Albanian, but in its vocalic aspect in Ancient Greek as [ɐ]; for example *h₂énh₁mos “breath” > Armenian հողմ hoɫm [hɔʁm] but Ancient Greek ἄνεμος ánemos.

*h₃ was at an early stage [ʕ] — more specifically [ɔ̙̆]. Because it was not voiceless, its pharyngeal quality requires a retracted tongue root, the backness of which is enhanced by lip rounding. In other words, its lower F2 and F3 may be achieved by a combination of tongue retraction and/or lip rounding, as in Arabic loanwords in Uzbek, Gulf Arabic, and Mombassan Swahili. Even if its lower F2 and F3 were articulated by tongue retraction without lip-rounding, a listener or infant learner might reinterpret its lower F2 and F3 as being due to lip-rounding, and a change in pronunciation thus develop. Consequently, *h₃ survived as a rounded vowel in Ancient Greek ὄις [oís], Latin ovis, Bosnian ovca < e.g. *h₃éu-i-s [howis] “ewe”. We don't have any "legacy" survivals of *h₃ as a consonant, so the inference that it was an approximant and not just a vowel comes primarily from the evidence of its phonological distribution (its position in syllables and words).

| Previous: Vowels |

Next: References |